An exploration of vision, reality and illusion

Jan van Eyck’s ‘Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele’

By Philip McCouat For readers' comments on this article, see here

Paintings are illusions. The arrangement of paint on a flat surface may be made to represent outer or inner worlds, concepts or experiences, but these are of course only illusory representations, not the “real” thing. As artist René Magritte famously stated in his 1929 painting of a pipe (The Treachery of Images), “this is not a pipe”. Picasso went further, saying “art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realise truth” [1]

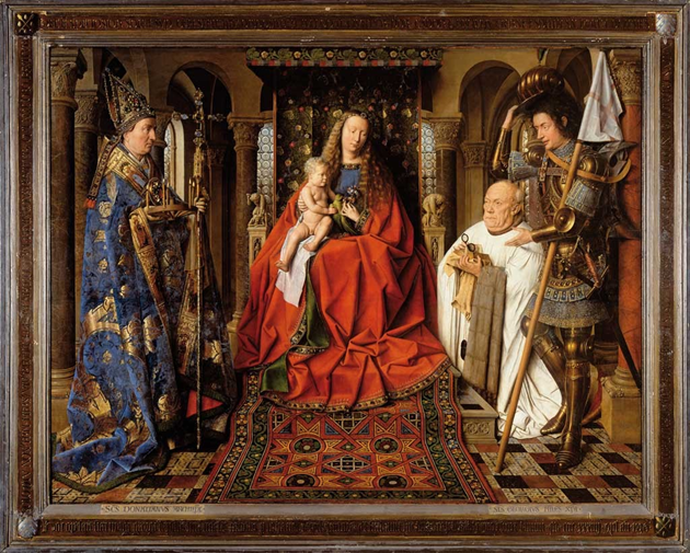

It follows that the more “realistic” a painting appears, the greater the illusion. Perhaps no artist better exemplifies this than the 15th century Netherlandish prodigy Jan van Eyck, and no painting more boldly embodies it than his Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele, a work which has been described as “arguably the most elaborate and impressive demonstration of the artist’s fascination with optical concepts and effects” [2]. So, it is this intriguing painting which we shall be exploring in this article.

Paintings are illusions. The arrangement of paint on a flat surface may be made to represent outer or inner worlds, concepts or experiences, but these are of course only illusory representations, not the “real” thing. As artist René Magritte famously stated in his 1929 painting of a pipe (The Treachery of Images), “this is not a pipe”. Picasso went further, saying “art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realise truth” [1]

It follows that the more “realistic” a painting appears, the greater the illusion. Perhaps no artist better exemplifies this than the 15th century Netherlandish prodigy Jan van Eyck, and no painting more boldly embodies it than his Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele, a work which has been described as “arguably the most elaborate and impressive demonstration of the artist’s fascination with optical concepts and effects” [2]. So, it is this intriguing painting which we shall be exploring in this article.

How the painting came about

The painting, which would be one of van Eyck’s largest, was commissioned in 1434 by Joris van der Paele, the wealthy but unwell canon of the church of St Donatian in Bruges. Joris intended it as his legacy to the church, to ensure that he had his own memorial and ultimately (hopefully) his place in heaven.

At the time, van Eyck was at the height of his fame. Based in Bruges, he was held in high regard by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and apart from his painting activities was involved in several diplomatic missions. He is credited with introducing an unprecedented combination of extraordinary craftsmanship, observational skills and detailed naturalism into his art, brilliantly exploiting the depth, immediacy and intense colour that could be achieved using the recently-introduced medium of oil painting [3]. His achievement in this respect has been described as an artistic “conquest of the visible world” [4].

At the time, van Eyck was at the height of his fame. Based in Bruges, he was held in high regard by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, and apart from his painting activities was involved in several diplomatic missions. He is credited with introducing an unprecedented combination of extraordinary craftsmanship, observational skills and detailed naturalism into his art, brilliantly exploiting the depth, immediacy and intense colour that could be achieved using the recently-introduced medium of oil painting [3]. His achievement in this respect has been described as an artistic “conquest of the visible world” [4].

The characters in the painting

Identification of the various characters in the painting is simplified by the fact that the painting’s frame, which has survived remarkably intact to the present day, is lined with a series of Latin inscriptions. These identify and comment on the characters in the painting and the circumstances in which the painting was made, and include van Eyck’s signature. The frame itself, incidentally, is not bronze, but painted by van Eyck so as to appear so, and the inscriptions are not incised into the frame, but instead painted so as to appear as if they were.

Joris, the patron, is depicted on the right in the painting [5], kneeling in his white surplice, rather awkwardly holding a book – presumably a book of prayers or a Book of Hours -- which he would have carried about with him as a girdle book [6]. Van Eyck does not appear to have flattered his patron -- Joris looks every bit of his 65 years, and there has been much modern speculation about his illness, though it appears that acute arm and shoulder pain, plus a potentially malignant lip lesion (painted over in a 1934 “restoration”) may have had significant impacts [7]. Whatever his affliction was, however, he would go on to survive for another nine years, and in fact ended up outliving the artist.

Joris, the patron, is depicted on the right in the painting [5], kneeling in his white surplice, rather awkwardly holding a book – presumably a book of prayers or a Book of Hours -- which he would have carried about with him as a girdle book [6]. Van Eyck does not appear to have flattered his patron -- Joris looks every bit of his 65 years, and there has been much modern speculation about his illness, though it appears that acute arm and shoulder pain, plus a potentially malignant lip lesion (painted over in a 1934 “restoration”) may have had significant impacts [7]. Whatever his affliction was, however, he would go on to survive for another nine years, and in fact ended up outliving the artist.

Joris seems to be looking abstractedly into the distance across to the left, perhaps to indicate that he is experiencing some sort of religious transport or waking dream, possibly inspired by what he has just read or prayed [8].

He holds a pair of spectacles, a status symbol at the time, indicating to us that he is both educated and devout, while also perhaps suggesting his human fallibility (or humility) in the sacred gathering that he finds himself in.

He holds a pair of spectacles, a status symbol at the time, indicating to us that he is both educated and devout, while also perhaps suggesting his human fallibility (or humility) in the sacred gathering that he finds himself in.

|

It seems that he was short-sighted, and had been using the convex-lensed spectacles as de facto magnifiers of the text of his book [9], and metaphorically magnifying his understanding of the religious message that it contained [10]. This is a very early representation of spectacles in art and, characteristically, Van Eyck, with his deep interest in optical effects, seizes on the chance to depict them in detail – you can even see the shadow of part of the frame on the open page of the book, and way that the lens has slightly distorted the text beneath it [11].

|

Apart from Joris, there are four other people in the small, chapel-like space. In the centre, the serene, golden-haired Virgin Mary sits on an elevated throne, below a finely-detailed brocade canopy (“baldachin”), patterned with white roses, indicating purity. According to a notation on the painting’s frame, she is “the echo of the eternal light, the immaculate reflection of God’s majesty”.

Mary is wearing a voluminous red gown, lined in green, and is nursing on her lap a blond, curly-headed and naked infant Jesus, who sits on a rather practical white towel [12]. Both she and Jesus hold the same little bunch of red, white and blue flowers. Perhaps oddly, Jesus also holds a green parrot (possibly a rose-ringed parakeet), which is also sitting on Mary’s lap, the colour of its tailfeathers echoing the green lining on Mary’s gown. Commentators have tied themselves into knots trying to explain the presence of the parrot -- it has been interpreted variously as a general symbol of Mary, as a symbol of virginity, the immaculate conception, the word of God (as parrots can miraculously “talk”), or God’s incarnation as a human in the form of Jesus [13].

Mary looks calmly and possibly rather fondly in the direction of Joris, though Jesus seems just as concerned with the parrot. In the foreground, the steps leading up to the Virgin’s throne are covered in a richly-patterned oriental carpet rendered with an extraordinary level of realistic detail.

Standing next to Joris is a young-looking, extravagantly armour-clad St George, presumably chosen to appear here because he is Joris’ name saint -- the name “Joris” is the Dutch form of “George” [14]. The saint, with his curved metal shield strapped to his back, is holding a flag bearing his traditional red cross on a white background. The word ADONAI, a Hebrew name for Lord, appears on his breastplate, identifying him, in the words inscribed on the frame, as a “soldier of Christ”.

Mary looks calmly and possibly rather fondly in the direction of Joris, though Jesus seems just as concerned with the parrot. In the foreground, the steps leading up to the Virgin’s throne are covered in a richly-patterned oriental carpet rendered with an extraordinary level of realistic detail.

Standing next to Joris is a young-looking, extravagantly armour-clad St George, presumably chosen to appear here because he is Joris’ name saint -- the name “Joris” is the Dutch form of “George” [14]. The saint, with his curved metal shield strapped to his back, is holding a flag bearing his traditional red cross on a white background. The word ADONAI, a Hebrew name for Lord, appears on his breastplate, identifying him, in the words inscribed on the frame, as a “soldier of Christ”.

According to tradition, St George was originally a soldier in the Roman army who was sentenced to death for refusing to recant his Christian faith. Much later he was immortalised in the legend of St George and the dragon, and became the patron saint of various countries and cities, including England, Ukraine and Ethiopia. In the painting, his task is to introduce Joris to the Virgin and Jesus. He has raised his shining ribbed metal helmet, topped with a jaunty red and green feather [15], as a mark of respect and greeting, and he gestures a little tentatively with his left hand. Though he is the only armed character in the painting, he appears to be the most nervous.

|

Across on the left of the painting is the rather stern-faced St Donatian, representing the Bruges church that bears his name and holds his relics. This was Joris’ own home church, and the church in which the painting would be hung. Donatian was a 4th century French saint and bishop of Reims. According to a variously-embroidered legend he had been thrown as child into a river (the Tiber), but survived due to the intervention of a holy man (maybe Pope Dionysius) who took five candles and placed them on a water wheel which either provided the light for the boy to be rescued, or something to hold onto as a float.

Here Donatian appears, dressed in a glittering blue and gold brocade cloak (“cope”), decorated with floral designs and images of saints, with a flash of red lining visible at his feet. On his head he wears an elaborate jewel-encrusted ceremonial headgear (“mitre”) [16], holding a spear-like jewelled processional cross (“crosier”) and, in his right hand, his legendary wheel with the five lighted candles. It is quite striking how the faces of both St Donatian and St George, who obviously would not have been personally known to the artist, are highly individualised, painted just as believably and naturistically as the face of Joris, adding to the illusion of verisimilitude of the scene. |

It is also notable that the colours of the characters’ clothes – St Donation in blue, Mary in red, and Joris and St George in white and gold, match the heraldic colours of Bruges [17].

The setting

The painting is set in what appears to be an intimately sized semicircular chapel, flanked by pillars and a series of arches. Further back is a walkway with narrow leaded windows. It is not clear whether this was intended to be an actual setting, or an amalgam, or entirely fictional. Indeed, although at first glance the architecture seems perfectly regular and ordered, there are some puzzling aspects -- the columns on the right vary in colour from brown to red, and the spacing between the columns, particularly in the nearest two columns on the right, is surprisingly tiny. The nearest column on the left also seems out of alignment with other columns on that side, and there is an initially-confusing arrangement of the arches at top right.

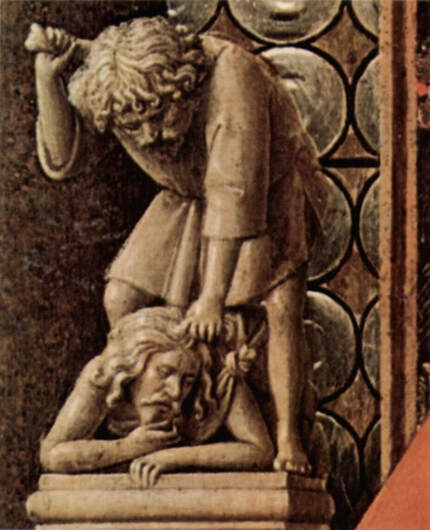

The throne on which Mary sits is decorated with carvings of scenes from the Bible, cleverly painted so as to resemble real carvings, intended to remind viewers of various religious messages -- the mercy of God, redemption from sin and the power of faith. On the face of the upright at left, at armrest height and partly obscured by Mary’s red cloak, is a carving of Adam. Above this, on top of the upright, is a carving of Cain beating Abel to death with a club. On the face of the corresponding upright at right is a carving of Eve and, above this, Samson is depicted as opening a lion’s jaws. Various instructive Old Testament scenes, including Abraham sacrificing Isaac, also appear in the carved capitals on top of the larger columns in the background.

The throne on which Mary sits is decorated with carvings of scenes from the Bible, cleverly painted so as to resemble real carvings, intended to remind viewers of various religious messages -- the mercy of God, redemption from sin and the power of faith. On the face of the upright at left, at armrest height and partly obscured by Mary’s red cloak, is a carving of Adam. Above this, on top of the upright, is a carving of Cain beating Abel to death with a club. On the face of the corresponding upright at right is a carving of Eve and, above this, Samson is depicted as opening a lion’s jaws. Various instructive Old Testament scenes, including Abraham sacrificing Isaac, also appear in the carved capitals on top of the larger columns in the background.

All figures in the chapel appear to be portrayed on the same scale, unlike many earlier commissioned portraits where the patron was typically shown in a smaller scale. In fact, the large size of the figures relative to the size of the chapel, together with the inclusion of the oriental carpet, make the space appear more cramped than it normally would. The integration of the donor and saints into the same sacred space, rather than being relegated to the side, was also unusual, and possibly unprecedented for the time [18].

This intimacy of the setting is emphasised by its insulation from the outside world; even the windows, narrow as they are, are fitted with distorting leaded glass [19]. It is further enhanced by the fact that all five figures are physically connected in some way – bizarrely, St George is actually standing with one foot on the hem of Joris’ flowing surplice (see Fig 5), which itself drapes against Mary’s red cloak. Jesus of course is on her lap, and at left, her cloak touches against St Donatian’s cloak.

This intimacy of the setting is emphasised by its insulation from the outside world; even the windows, narrow as they are, are fitted with distorting leaded glass [19]. It is further enhanced by the fact that all five figures are physically connected in some way – bizarrely, St George is actually standing with one foot on the hem of Joris’ flowing surplice (see Fig 5), which itself drapes against Mary’s red cloak. Jesus of course is on her lap, and at left, her cloak touches against St Donatian’s cloak.

Light and reflection

All the characters are brilliantly lit by an imaginary source somewhere over the viewer’s left shoulder, forming a sharp contrast to the much gloomier architectural background. The light highlights the many reflective objects in the painting, such as the glittering gold brocade thread of St Donatian’s cope and the highly polished accoutrements of St George, the only holy person who fully faces the light. His polished helmet reflects the light coming in from the windows, which it would do if he was actually in the depicted room. It also reflects distorted images of the Virgin and child in each of its metal curves, and the top of the metal shield on St George’s back, though inconspicuous, subtly reflects part of the red-crossed flag.

Van Eyck’s own tiny self-portrait – a rare example of the genre at the time – also appears as a reflection on St George’s shield. It depicts the artist himself wearing a red turban at work on his easel, but it’s hard to find unless you know where to look (Fig 9). Van Eyck uses a rather similar device with a mirror on the back wall in his Arnolfini Portrait (Fig 10), though in that case, it was entirely physically possible that the mirror could reflect the painter, who in reality was in the same room and at the same time as the subjects of the painting. However, in the present painting, it is of course quite impossible for him to really be reflected in St George’s helmet – not only because St George is not actually there in the room (or maybe not anywhere at all), but also because the artist certainly wasn’t with him there either. Paradoxically, however, such a bold illusion, piled on another bold illusion, still ends up giving an impression of added verisimilitude to the painting [20].

Illusion, faith and reality

Joris died in 1443 and, according to his last wishes, was buried in the church at Bruges. This was also the final resting place of Jan van Eyck who had passed away two years earlier.

After his death, the painting itself, which possibly may have been being held by Joris at his home [21], was presented to the church, where it became a major attraction. From then on, it had a checkered history, being moved to safety during a period of unrest, then returned to the church, where it was hung variously as the main altarpiece, then moved to the sacristy, then to a new side altar. Later, it was plundered during the French Revolution and sent to the Louvre, only finally returning to Bruges in 1816, where, as a result of the church’s demolition in 1800, it was transferred to the Groeninge Museum. Apart from one brief period when it was sent secretly to Brussels to safeguard it from Nazi appropriation [21A], it has stayed in Bruges as a star attraction ever since.

Today, we can look at this painting in the Museum in an academic way, maybe regarding it as an impressive manifestation of a dream or vision, and analysing the artist’s astonishing skill in creating such a realistic and convincing illusion. But, of course, few viewers today would believe that, in reality, this holy gathering of five characters -- from totally different time periods, and with widely-varying degrees of historicity -- could ever really have existed together in the same place, let alone having the artist handily being present there too.

However, if we go back to the 15th century, a time of unconditional faith, the lines between reality, illusion and faith were not so clear-cut. Imagine the reaction of a person who looked at this painting of Joris in those times, and may even have known him in real-life. They would see a life-like image of seemingly miraculous precision and detail, showing holy persons very familiar to them, hanging in the church which bore the name and relics of one of them -- the same church where Joris himself had worked and which he had endowed and where he lay buried -- while masses funded by Joris are being held in that church for his ultimate salvation [22]. Such an experience could have been totally profound, one in which the lines between truth, illusion, faith and reality cease to have much relevance ■

© Philip McCouat 2023. First published July 2023

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, “An exploration of vision, reality and illusion: Jan van Eyck’s ‘Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele’”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

After his death, the painting itself, which possibly may have been being held by Joris at his home [21], was presented to the church, where it became a major attraction. From then on, it had a checkered history, being moved to safety during a period of unrest, then returned to the church, where it was hung variously as the main altarpiece, then moved to the sacristy, then to a new side altar. Later, it was plundered during the French Revolution and sent to the Louvre, only finally returning to Bruges in 1816, where, as a result of the church’s demolition in 1800, it was transferred to the Groeninge Museum. Apart from one brief period when it was sent secretly to Brussels to safeguard it from Nazi appropriation [21A], it has stayed in Bruges as a star attraction ever since.

Today, we can look at this painting in the Museum in an academic way, maybe regarding it as an impressive manifestation of a dream or vision, and analysing the artist’s astonishing skill in creating such a realistic and convincing illusion. But, of course, few viewers today would believe that, in reality, this holy gathering of five characters -- from totally different time periods, and with widely-varying degrees of historicity -- could ever really have existed together in the same place, let alone having the artist handily being present there too.

However, if we go back to the 15th century, a time of unconditional faith, the lines between reality, illusion and faith were not so clear-cut. Imagine the reaction of a person who looked at this painting of Joris in those times, and may even have known him in real-life. They would see a life-like image of seemingly miraculous precision and detail, showing holy persons very familiar to them, hanging in the church which bore the name and relics of one of them -- the same church where Joris himself had worked and which he had endowed and where he lay buried -- while masses funded by Joris are being held in that church for his ultimate salvation [22]. Such an experience could have been totally profound, one in which the lines between truth, illusion, faith and reality cease to have much relevance ■

© Philip McCouat 2023. First published July 2023

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, “An exploration of vision, reality and illusion: Jan van Eyck’s ‘Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele’”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

Endnotes

[1] Dore Ashton, Picasso on Art (1972) “Two statements by Picasso”

[2] Stephen Hanley, “Optical Symbolism as Optical Description: A Study of Canon van der Paele’s Spectacles”, Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 1:1 (Winter 2009)

[3] For oil paintings, pigments were mixed with linseed oil, giving them a radiant, transparent shine. Previously, most artists used tempera, a mixture of natural pigments with egg yolk, which gave a soft opaque effect. Van Eyck is sometimes credited as the actual inventor or oil painting (for example, by the 16th century art historian/critic Giorgio Vasari), but it appears that this is not correct: Anne van Oosterwijk, “Madonna with Canon Van der Paele”, Flemish Primitives https://vlaamseprimitieven.vlaamsekunstcollectie.be/en/research/webpublications/madonna-with-canon-joris-van-der-paele/

[4] G.T. Faggin, “La conquete du monde visible”, in Chefs-Doeuvre de L’Art: Grands Peintres: Van Eyck, Hachette, Paris 1966

[5] The coats of arms of his family members also appear in the frame’s corners.

[6] This is a type of portable book whose bindings extend into a tapered attachment for the wearer’s belt/girdle

[7] On the lip lesion, see Massimo Papi, "The importance of the details: The curious dermatologic story of the Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele by van Eyck", Clinics in Dermatology, 39 (6): 1095–1099

[8] Craig Harbison, “Visions and Meditations in Early Flemish Painting,” Simiolus 15 (1985): 101

[9] Concave lenses, suitable for improving farsightedness, were not invented till later

[10] The spectacles do not have earpieces, as these were not invented till much later

[11] Hanley, op cit

[12] Possibly, this was intended to suggest the white cloth placed on the altar as part of the ceremony of the Eucharist

[13] Miyako Sugiyama, “The Symbolism of the Parrot in Jan van Eyck’s Virgin and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele”, The Japan Art History Society, 176 p224

[14] The church also apparently held a relic of one of his arm bones

[15] It is cut-off part-way at the upper edge of the painting

[16] The cope and mitre accord exactly with the description of these garments in the church’s own historical inventories: Oosterwijk, op cit

[17] Oosterwijk, op cit

[18] This type of grouping in a painting became known as a “sacre conversazione” or holy conversation

[19] This contrasts with the composition of his later work The Virgin of Chancellor Nicolas Rolin (1437)

[20] Laura Cumming, A Face to the World, HarperPress, London, 2009 at 13-15

[21] Barbara G Lane, “The Case of Canon van der Paele”, Notes in the History of Art, vol. 9, no. 2, 1990, pp. 1–6.

[21A] Lynn A. Nicholas, The Rape of Europa, Macmillan, London 1995 at 295.

[22] See also Douglas Brine, “Jan van Eyck, Canon van der Paele, and the Art of Commemoration”, The Art Bulletin, September 2014

© Philip McCouat 2023. First published July 2023

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, “An exploration of vision, reality and illusion: Jan van Eyck’s ‘Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele’”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

[2] Stephen Hanley, “Optical Symbolism as Optical Description: A Study of Canon van der Paele’s Spectacles”, Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 1:1 (Winter 2009)

[3] For oil paintings, pigments were mixed with linseed oil, giving them a radiant, transparent shine. Previously, most artists used tempera, a mixture of natural pigments with egg yolk, which gave a soft opaque effect. Van Eyck is sometimes credited as the actual inventor or oil painting (for example, by the 16th century art historian/critic Giorgio Vasari), but it appears that this is not correct: Anne van Oosterwijk, “Madonna with Canon Van der Paele”, Flemish Primitives https://vlaamseprimitieven.vlaamsekunstcollectie.be/en/research/webpublications/madonna-with-canon-joris-van-der-paele/

[4] G.T. Faggin, “La conquete du monde visible”, in Chefs-Doeuvre de L’Art: Grands Peintres: Van Eyck, Hachette, Paris 1966

[5] The coats of arms of his family members also appear in the frame’s corners.

[6] This is a type of portable book whose bindings extend into a tapered attachment for the wearer’s belt/girdle

[7] On the lip lesion, see Massimo Papi, "The importance of the details: The curious dermatologic story of the Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele by van Eyck", Clinics in Dermatology, 39 (6): 1095–1099

[8] Craig Harbison, “Visions and Meditations in Early Flemish Painting,” Simiolus 15 (1985): 101

[9] Concave lenses, suitable for improving farsightedness, were not invented till later

[10] The spectacles do not have earpieces, as these were not invented till much later

[11] Hanley, op cit

[12] Possibly, this was intended to suggest the white cloth placed on the altar as part of the ceremony of the Eucharist

[13] Miyako Sugiyama, “The Symbolism of the Parrot in Jan van Eyck’s Virgin and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele”, The Japan Art History Society, 176 p224

[14] The church also apparently held a relic of one of his arm bones

[15] It is cut-off part-way at the upper edge of the painting

[16] The cope and mitre accord exactly with the description of these garments in the church’s own historical inventories: Oosterwijk, op cit

[17] Oosterwijk, op cit

[18] This type of grouping in a painting became known as a “sacre conversazione” or holy conversation

[19] This contrasts with the composition of his later work The Virgin of Chancellor Nicolas Rolin (1437)

[20] Laura Cumming, A Face to the World, HarperPress, London, 2009 at 13-15

[21] Barbara G Lane, “The Case of Canon van der Paele”, Notes in the History of Art, vol. 9, no. 2, 1990, pp. 1–6.

[21A] Lynn A. Nicholas, The Rape of Europa, Macmillan, London 1995 at 295.

[22] See also Douglas Brine, “Jan van Eyck, Canon van der Paele, and the Art of Commemoration”, The Art Bulletin, September 2014

© Philip McCouat 2023. First published July 2023

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, “An exploration of vision, reality and illusion: Jan van Eyck’s ‘Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele’”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME