Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night

|

By Philip McCouat

This article is about three traditional occupations of the night. These were far from the seductive occupations of discretionary leisure or pleasure. Rather, all three involved essential functions, and they ranged all the way from uncomfortable, to distasteful, to horrific. As might be expected, there were radical differences in the way in which the public viewed practitioners of each of the occupations – and even the ways in which the practitioners saw themselves – and these were reflected in the popular art and writings of the time. Here, we’ll be looking at each of these now long-gone occupations – the watchmen, the “nightmen” and the plague corpse-bearers of London. We’ll also be analysing how they were perceived, and how accurate those perceptions may have been. |

For more on diseases

For more articles on art and disease, see:

|

The watchmen

It has been claimed that the nightwatch, not prostitution, is the world’s most ancient occupation, originating as soon as men and women first feared the darkness [1]. Certainly it continued for centuries right up until the 19th century. In London, despite its manifest inadequacies, it continued with surprisingly few changes, even though periodic attempts were made to regularise and improve it. One of the most notable of these was the 1663 legislation passed during the reign of Charles II, a circumstance which gave rise to the watchmen’s semi-affectionate, semi-sarcastic nickname of “Charlies” (or "Charleys").

Initially, it had been the civic duty of able-bodied townsmen periodically to provide watch services, with little or no compensation. As might be expected, this obligation was not popular – the job was inconvenient, unrewarding, time-consuming and alternately dangerous or boring [2]. As time went by, the more wealthy paid to have substitutes act for them, or even just opted to pay a fine for non-attendance. Eventually, the duty to serve was replaced by a parish levy out of which “professional” watchmen would be paid.

These London watchmen patrolled the streets of the parish, typically between the hours of 9 pm to 6 am, following a set route. Not having uniforms, they adopted a common garb of a greatcoat or cloak, often with a battered hat, and were “armed” with a lantern, a staff and a rattle to attract attention. They were provided with a watch box, usually wooden, to shelter or rest in (Fig 1).

Initially, it had been the civic duty of able-bodied townsmen periodically to provide watch services, with little or no compensation. As might be expected, this obligation was not popular – the job was inconvenient, unrewarding, time-consuming and alternately dangerous or boring [2]. As time went by, the more wealthy paid to have substitutes act for them, or even just opted to pay a fine for non-attendance. Eventually, the duty to serve was replaced by a parish levy out of which “professional” watchmen would be paid.

These London watchmen patrolled the streets of the parish, typically between the hours of 9 pm to 6 am, following a set route. Not having uniforms, they adopted a common garb of a greatcoat or cloak, often with a battered hat, and were “armed” with a lantern, a staff and a rattle to attract attention. They were provided with a watch box, usually wooden, to shelter or rest in (Fig 1).

As the watchmen patrolled, they loudly announced the weather and called the time every hour, on the hour. The cry became immortalised in the traditional watchman’s song The Waits:

Past three o'clock! Young maidens are sleeping,

Scarcely they close their bright beaming eyes;

May our soft numbers cheer you, but break not

Innocent slumbers, hear us but wake not!

Past three o’clock, and a cold frosty morning

Past three o’ clock, good morrow, Masters all! [3]

The watchmen also kept a lookout for fires, and checked that occupiers had locked their doors. Samuel Pepys, back in 1663, recorded how “this morning, about two or three o’clock, [I was] knocked up in our back yard [ie by the watchman knocking on the door with his staff], and rising to the window, being moonshine, I found it was the constable and his watch, who had found our back yard door open, and so came in to see what the matter was. So I desired them to shut the door, and bid them good night, and so to bed again” [4].

For a small fee, a watchman might act as a mobile alarm clock (real ones were not invented until later), stopping at houses along his route, to waken anyone who needed to be up at a specific time [5]. Importantly, they were expected to keep an eye out for suspicious or offending people, and “if they meet with any persons they suspect of ill designs, drunkards, prostitutes, vagrants and other disorderly persons, they are empowered to carry them before the constable at his watch house”[6]. As can be seen, these were general duties of maintaining some sort of general public order – watchmen were not the type of person that would be expected to catch murderers or serious criminals [7].

An unfortunate reputation

The watchmen’s meagre wages and the unpleasant (though important) aspects of their duties continued to attract a low quality of candidates, and complaints about their performance continued to grow. The watchmen became a common butt of ridicule, and even contempt, due to the unfortunate reputation that they had acquired of being old, decrepit, lazy, drunk, corrupt and ineffectual. This attitude dated back at least to Shakespearian times. In Much Ado About Nothing, the playwright has a watchman say, “We would rather sleep than talk: we know what belongs to a watch”. In this scene, the watch constable Dogberry comically counsels the watchmen to take the easiest and most ineffectual way in dealing with any problem. So, for example, he urges that if you hear a child cry in the night and the nurse cannot be stirred, “depart in peace, and let the child wake her with crying”; if you come upon drunkard, you are to bid them to “get to bed, and if they do not, let them alone till they are sober”; and “the most peaceful way for you if you do take a thief, is to let him show himself for what he is and steal out of your company” [8]. The name Dogberry has itself come to mean any foolish, blundering or stupid official.

Watchmen clearly had an image problem, and over time, the critical jokes and comments built up. Watchmen were variously described ”old, poore, weake and unhable”; “old frowzy, croaking sots, too infirm and lame to walk without their staves” [9], and chosen “out of those poor, old decrepit people who are for want of bodily strength rendered incapable of getting a livelihood by work” [10].

Even the watchmen’s regular calling of the hour became a sore point. Despite the plaintive hope in the earlier quoted watchmen’s song to “hear us but wake not”, the effect was described as “every hour of the night they waken people by shouting to them that they hope they are sleeping well” [11]. In his classic tale Humphrey Clinker (1771), Smollett has a long-suffering character say, “I start every hour from my sleep, at the horrid noise of the watchmen bawling the hour through every street, and thundering at every door; a set of useless fellows, who serve no other purpose but that of disturbing the repose of the inhabitants” [12]. Robert Southey comments on this “strange custom of paying people to tell them what the weather is every hour during the night, till they get accustomed to the noise, that they sleep on and cannot hear what is said” [13].

In 1821, the generally-expressed public impression of watchmen was reflected in a mock advertisement that stated: “Wanted, a hundred thousand men for London watchmen. None need apply to this lucrative situation without being the age of sixty, seventy, eighty, or ninety years; blind with one eye, and seeing very little with the other; crippled with one or both legs; deaf as a post; with an asthmatical cough, that tears them to pieces; whose speed will keep pace with a snail, and the strength of whose am will not be able to arrest an old washerwoman of fourscore returned from a hard day’s fag at the wash-tub...and such that will neither hear nor see what belongs to their duty, or what does not, unless well palmed or garnished for the same”[14].

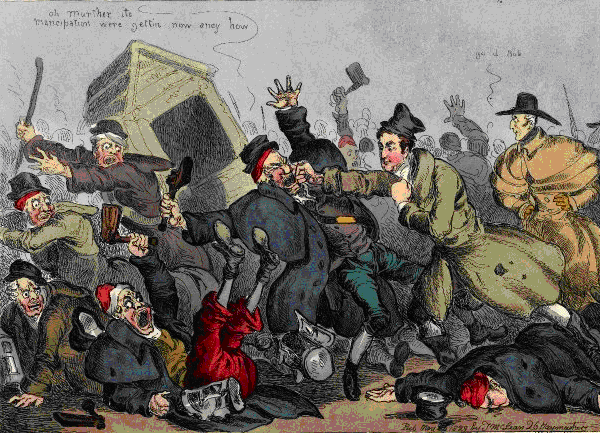

Sometimes the comments and jokes at the watchmen’s expense became physical. In his wildly popular 1821 book, Life in London [15], Pierce Egan describes the riotous escapades of three dashing young men, Jerry Hawthorn. and his elegant friend Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, “in their rambles and sprees through the metropolis”. Among all the predictable drinking, gambling, whoring and other wearily laddish pranks, the book featured one of their favourite pastimes – creeping up behind a watchman’s watch box and tipping it over while he was still inside it. This was duly celebrated in song:

And as we were rolling along, Sir

A Night Guardian we found fast asleep

When we down’d him with his box in a minute

And tumbled the old Charley in the Street!

Fal de dal, de dal, de dal [etc]

Complete with illustrations (Fig 2), this dubious achievement became known as doing a “Tom and Jerry”, and even became a standard segment in street marionette shows. The respected commentator Henry Mayhew quotes one well-known puppeteer, the “Fantoccini Man”, as describing part of his performance of “a scene in Tom and Jerry. The curtain winds up, and there’s a watchman prowling the streets, and some of those larking gentlemen comes on and pitch into him. He looks round and he can’t see anybody. Presently another comes in and gives him another knock, and then there’s a scuffle, and off they go over the watch-box, and down comes the scone. That makes the juveniles laugh, and finishes up the whole performance merry like”[16].

Past three o'clock! Young maidens are sleeping,

Scarcely they close their bright beaming eyes;

May our soft numbers cheer you, but break not

Innocent slumbers, hear us but wake not!

Past three o’clock, and a cold frosty morning

Past three o’ clock, good morrow, Masters all! [3]

The watchmen also kept a lookout for fires, and checked that occupiers had locked their doors. Samuel Pepys, back in 1663, recorded how “this morning, about two or three o’clock, [I was] knocked up in our back yard [ie by the watchman knocking on the door with his staff], and rising to the window, being moonshine, I found it was the constable and his watch, who had found our back yard door open, and so came in to see what the matter was. So I desired them to shut the door, and bid them good night, and so to bed again” [4].

For a small fee, a watchman might act as a mobile alarm clock (real ones were not invented until later), stopping at houses along his route, to waken anyone who needed to be up at a specific time [5]. Importantly, they were expected to keep an eye out for suspicious or offending people, and “if they meet with any persons they suspect of ill designs, drunkards, prostitutes, vagrants and other disorderly persons, they are empowered to carry them before the constable at his watch house”[6]. As can be seen, these were general duties of maintaining some sort of general public order – watchmen were not the type of person that would be expected to catch murderers or serious criminals [7].

An unfortunate reputation

The watchmen’s meagre wages and the unpleasant (though important) aspects of their duties continued to attract a low quality of candidates, and complaints about their performance continued to grow. The watchmen became a common butt of ridicule, and even contempt, due to the unfortunate reputation that they had acquired of being old, decrepit, lazy, drunk, corrupt and ineffectual. This attitude dated back at least to Shakespearian times. In Much Ado About Nothing, the playwright has a watchman say, “We would rather sleep than talk: we know what belongs to a watch”. In this scene, the watch constable Dogberry comically counsels the watchmen to take the easiest and most ineffectual way in dealing with any problem. So, for example, he urges that if you hear a child cry in the night and the nurse cannot be stirred, “depart in peace, and let the child wake her with crying”; if you come upon drunkard, you are to bid them to “get to bed, and if they do not, let them alone till they are sober”; and “the most peaceful way for you if you do take a thief, is to let him show himself for what he is and steal out of your company” [8]. The name Dogberry has itself come to mean any foolish, blundering or stupid official.

Watchmen clearly had an image problem, and over time, the critical jokes and comments built up. Watchmen were variously described ”old, poore, weake and unhable”; “old frowzy, croaking sots, too infirm and lame to walk without their staves” [9], and chosen “out of those poor, old decrepit people who are for want of bodily strength rendered incapable of getting a livelihood by work” [10].

Even the watchmen’s regular calling of the hour became a sore point. Despite the plaintive hope in the earlier quoted watchmen’s song to “hear us but wake not”, the effect was described as “every hour of the night they waken people by shouting to them that they hope they are sleeping well” [11]. In his classic tale Humphrey Clinker (1771), Smollett has a long-suffering character say, “I start every hour from my sleep, at the horrid noise of the watchmen bawling the hour through every street, and thundering at every door; a set of useless fellows, who serve no other purpose but that of disturbing the repose of the inhabitants” [12]. Robert Southey comments on this “strange custom of paying people to tell them what the weather is every hour during the night, till they get accustomed to the noise, that they sleep on and cannot hear what is said” [13].

In 1821, the generally-expressed public impression of watchmen was reflected in a mock advertisement that stated: “Wanted, a hundred thousand men for London watchmen. None need apply to this lucrative situation without being the age of sixty, seventy, eighty, or ninety years; blind with one eye, and seeing very little with the other; crippled with one or both legs; deaf as a post; with an asthmatical cough, that tears them to pieces; whose speed will keep pace with a snail, and the strength of whose am will not be able to arrest an old washerwoman of fourscore returned from a hard day’s fag at the wash-tub...and such that will neither hear nor see what belongs to their duty, or what does not, unless well palmed or garnished for the same”[14].

Sometimes the comments and jokes at the watchmen’s expense became physical. In his wildly popular 1821 book, Life in London [15], Pierce Egan describes the riotous escapades of three dashing young men, Jerry Hawthorn. and his elegant friend Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, “in their rambles and sprees through the metropolis”. Among all the predictable drinking, gambling, whoring and other wearily laddish pranks, the book featured one of their favourite pastimes – creeping up behind a watchman’s watch box and tipping it over while he was still inside it. This was duly celebrated in song:

And as we were rolling along, Sir

A Night Guardian we found fast asleep

When we down’d him with his box in a minute

And tumbled the old Charley in the Street!

Fal de dal, de dal, de dal [etc]

Complete with illustrations (Fig 2), this dubious achievement became known as doing a “Tom and Jerry”, and even became a standard segment in street marionette shows. The respected commentator Henry Mayhew quotes one well-known puppeteer, the “Fantoccini Man”, as describing part of his performance of “a scene in Tom and Jerry. The curtain winds up, and there’s a watchman prowling the streets, and some of those larking gentlemen comes on and pitch into him. He looks round and he can’t see anybody. Presently another comes in and gives him another knock, and then there’s a scuffle, and off they go over the watch-box, and down comes the scone. That makes the juveniles laugh, and finishes up the whole performance merry like”[16].

Given the perceived deficiencies of the watchman system, it may be wondered why some more efficient and professional system was not put in place [17]. Apart from a predictable institutional lethargy, and cost considerations, the main reason appeared to have been the London public’s long-standing distrust of regulation and governmental interference. Ekirch comments that the creation of trained police was hindered by traditional fears of monarchical power, backed by fears of falling under despotic armed control [18]. There was a genuine fear that a police force would operate on the French model, with spies and agents provocateurs [19].

This attitude struck many observers as peculiar. One Russian visitor reflected that “the English have a dread of a strict constabulary, and prefer to be robbed rather than to see sentries and pickets”[20]. In Humphrey Clinker, Smollett has a character sarcastically refer to “the wise patriots of London [who] have taken it into their heads, that all regulation is inconsistent with liberty; and that every man ought to live in his own way, without restraint – nay, as there is not sense enough left among them, to be discomposed by the nuisance I have mentioned, they may, for aught I care, wallow in the mire of their own pollution” [21]. There may also have been a class element in this attitude; some of the “better” class of person may have had an aversion to being controlled by police whom they might regard as being their inferiors [22].

Despite this resistance, however, by the early 19th century the mounting evidence of inadequacy, coupled with steep increases in crime levels and rising levels of political and industrial disorder, prompted a series of committees of inquiry into the whole issue of law enforcement. The reform movement, led by Sir Robert Peel, eventually culminated in the introduction of a uniformed professional city-wide police force (“Peelers”) with the passing of 1829 Metropolitan Police Act, resulting in the effective dismantling of the watchman era in London [23].

A satirical print of the time depicts the London watchmen’s demise, showing Peel and other proponents of the Metropolitan Police Act, in their guise as “Tom”, “Jerry” and “Logic”, thoroughly routing a collection of elderly watchmen who are wielding lanterns, staffs and rattles (Fig 3).

This attitude struck many observers as peculiar. One Russian visitor reflected that “the English have a dread of a strict constabulary, and prefer to be robbed rather than to see sentries and pickets”[20]. In Humphrey Clinker, Smollett has a character sarcastically refer to “the wise patriots of London [who] have taken it into their heads, that all regulation is inconsistent with liberty; and that every man ought to live in his own way, without restraint – nay, as there is not sense enough left among them, to be discomposed by the nuisance I have mentioned, they may, for aught I care, wallow in the mire of their own pollution” [21]. There may also have been a class element in this attitude; some of the “better” class of person may have had an aversion to being controlled by police whom they might regard as being their inferiors [22].

Despite this resistance, however, by the early 19th century the mounting evidence of inadequacy, coupled with steep increases in crime levels and rising levels of political and industrial disorder, prompted a series of committees of inquiry into the whole issue of law enforcement. The reform movement, led by Sir Robert Peel, eventually culminated in the introduction of a uniformed professional city-wide police force (“Peelers”) with the passing of 1829 Metropolitan Police Act, resulting in the effective dismantling of the watchman era in London [23].

A satirical print of the time depicts the London watchmen’s demise, showing Peel and other proponents of the Metropolitan Police Act, in their guise as “Tom”, “Jerry” and “Logic”, thoroughly routing a collection of elderly watchmen who are wielding lanterns, staffs and rattles (Fig 3).

The question, however, remains: just how realistic were these seemingly uniformly negative descriptions of the watchmen and the constables made by commentators and in literature and art? More recent research by Ruth Paley suggests that the true situation was much more nuanced. For example, not all watchmen arrangements were ineffective. Although parish officials had no jurisdiction beyond their own borders, and there was a growing trend towards inter-parish cooperation. In addition, recruitment often involved attention to good character and physique, and involved an upper age limit.

An additional factor pointed out by Paley was that much of the comment, especially in the 1820s was highly partisan, fostered by proponents of Peels’ reform proposals. It was in those proponents’ interests to portray the much-ridiculed Charleys as an example of the patent inadequacies of existing law enforcement agents [24]. The picture was further complicated by the fact that there were major differences between parishes – some were competently policed, while others did not bother hiring watchmen at all unless a crime scare panicked residents into doing to until the scare blew over [25]. Taking all this into account, it is possible that the satirical art and racy literature fell all too readily into easy caricature – perhaps the Charleys were not quite so hopeless as they were so often depicted.

An additional factor pointed out by Paley was that much of the comment, especially in the 1820s was highly partisan, fostered by proponents of Peels’ reform proposals. It was in those proponents’ interests to portray the much-ridiculed Charleys as an example of the patent inadequacies of existing law enforcement agents [24]. The picture was further complicated by the fact that there were major differences between parishes – some were competently policed, while others did not bother hiring watchmen at all unless a crime scare panicked residents into doing to until the scare blew over [25]. Taking all this into account, it is possible that the satirical art and racy literature fell all too readily into easy caricature – perhaps the Charleys were not quite so hopeless as they were so often depicted.

The nightmen

While the watchmen’s job could only be performed at night, another occupation was performed at night simply because it was more convenient and less embarrassing to do so. This was the occupation of the “nightmen”. Their job was to empty Londoner’s privies.

During the 18th century, London’s sewage system was rudimentary at best [26]. Public toilets, or “houses of easement” were rare [27]. The great majority of private houses’ sewage (daintily called “nightsoil”) drained directly into a cesspool, typically situated directly under the privy (the “necessary house”), which was often in the backyard, as far from the living areas of the house as possible. The cesspit, which could be as much as twenty feet deep, was originally just a large excavation in the ground, but later it came to be lined with bricks, typically with a domed top and – in the better-off houses – an outlet valve for the liquid matter to seep away.

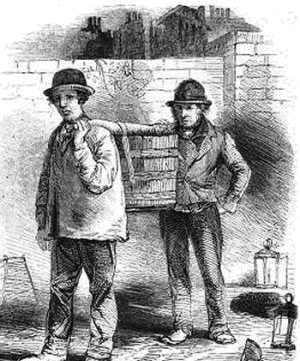

These pits obviously required periodical emptying (usually every few years), and this job was done by the nightmen [28], so-called because they were required by law to carry out their duties at night, usually between midnight and 5 am. Nightmen were also referred to as “nightsoil men”, “tom turd men” or, back in Tudor times, as “gong farmers”. The work was supplemented by the "goldfinders", "toshers", "mudlarks" and other scavengers who trawled the streets and filthy mud banks for any items – even lumps of coal – that they could resell [29]. There were even collectors of dog faeces ("pure") for use in the tanning process.

Unlike the situation with watchmen, removing the nightsoil was not organised by the parish or local government body. The nightmen were independent contractors, and the arrangements were reached by private agreement with the owner/landlord of the premises, as the occasion arose. In most London houses, few of which had rear access [30], the occupier would ensure that the door was left unlocked so that the nightmen could gain access down the hallway [31].

Five nightmen were usually required for each job. First, a holeman descended into the cesspit to fill the wooden tubs lowered by the ropeman. Then he would scrape or wash off the outside of the tub before the rope man would raise the tub. Two tubmen then carried the tubs, suspended on a pole, back and forth through the hall to the street, where the fifth man emptied the loads into a horse-drawn tanker cart [32]. As may be imagined, the job could be arduous and there are reports of some nightmen, or their assistants, being overcome or even dying from asphyxiation.

During the 18th century, London’s sewage system was rudimentary at best [26]. Public toilets, or “houses of easement” were rare [27]. The great majority of private houses’ sewage (daintily called “nightsoil”) drained directly into a cesspool, typically situated directly under the privy (the “necessary house”), which was often in the backyard, as far from the living areas of the house as possible. The cesspit, which could be as much as twenty feet deep, was originally just a large excavation in the ground, but later it came to be lined with bricks, typically with a domed top and – in the better-off houses – an outlet valve for the liquid matter to seep away.

These pits obviously required periodical emptying (usually every few years), and this job was done by the nightmen [28], so-called because they were required by law to carry out their duties at night, usually between midnight and 5 am. Nightmen were also referred to as “nightsoil men”, “tom turd men” or, back in Tudor times, as “gong farmers”. The work was supplemented by the "goldfinders", "toshers", "mudlarks" and other scavengers who trawled the streets and filthy mud banks for any items – even lumps of coal – that they could resell [29]. There were even collectors of dog faeces ("pure") for use in the tanning process.

Unlike the situation with watchmen, removing the nightsoil was not organised by the parish or local government body. The nightmen were independent contractors, and the arrangements were reached by private agreement with the owner/landlord of the premises, as the occasion arose. In most London houses, few of which had rear access [30], the occupier would ensure that the door was left unlocked so that the nightmen could gain access down the hallway [31].

Five nightmen were usually required for each job. First, a holeman descended into the cesspit to fill the wooden tubs lowered by the ropeman. Then he would scrape or wash off the outside of the tub before the rope man would raise the tub. Two tubmen then carried the tubs, suspended on a pole, back and forth through the hall to the street, where the fifth man emptied the loads into a horse-drawn tanker cart [32]. As may be imagined, the job could be arduous and there are reports of some nightmen, or their assistants, being overcome or even dying from asphyxiation.

Together with the watchmen and the early morning starters, the nightmen’s activities ensured that nighttimes could be quite noisy. Southey comments that “the clatter of the nightmen has scarcely ceased before that of the morning carts begins”[33].

Once collected, the nightsoil was taken to common land or official dumps, where, typically, it was mixed with used hops which had been bought cheaply from the breweries. It was then spread out to dry until it was in a condition to be sold as high-nitrogen fertiliser in fields or market gardens.. One London dump, “Mt Pleasant” at Clerkenwell, occupied over 7 acres [34]. This particular aspect of the nightmen’s business started to wind down once guano (or bird droppings), highly suitable as fertiliser, began to be imported cheaply from South America in 1847. Soon farmers found they could refuse to pay for human waste entirely, the nightmen being pleased to find anyone at all to take it.

As with watchmen, this whole system had always been fairly problematic. As far back as 1660, Samuel Pepys had been complaining about how the collapse of his neighbour’s retaining wall gave him an unpleasant surprise, when “going down into my cellar to look, I put my foot in to a great heap of turds, by which I find that Mr Turner’s house of office [cesspit] is full and comes into my cellar which troubles me”[35].

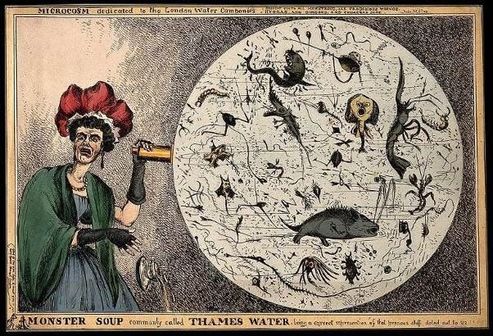

By the 1840s, it was unpleasantly obvious that the sewerage system had widespread and serious problems. The innovation of flush lavatories, while having its own attractions, had actually worsened the situation, as the water had the effect of filling up the cesspools “20 times as fast”, and with liquids, which made them more difficult to clean [36]. There were so many cesspools that the walls between them frequently collapsed, effectively forming “cess lakes”. The overflow liquid contaminated the ground, while the solids slowly seeped into neighbouring cellars and streets, oozing up through the bricks every time it rained. In St Giles, for example, it was reported that “whole areas of the cellars were full of nightsoil to the depth of three feet” and yards were “covered in nightsoil … to the depth of nearly six inches” [37].

Human waste was also being emptied via water draining tunnels into the Thames, with predictable results (Figs 5, 5A)

Once collected, the nightsoil was taken to common land or official dumps, where, typically, it was mixed with used hops which had been bought cheaply from the breweries. It was then spread out to dry until it was in a condition to be sold as high-nitrogen fertiliser in fields or market gardens.. One London dump, “Mt Pleasant” at Clerkenwell, occupied over 7 acres [34]. This particular aspect of the nightmen’s business started to wind down once guano (or bird droppings), highly suitable as fertiliser, began to be imported cheaply from South America in 1847. Soon farmers found they could refuse to pay for human waste entirely, the nightmen being pleased to find anyone at all to take it.

As with watchmen, this whole system had always been fairly problematic. As far back as 1660, Samuel Pepys had been complaining about how the collapse of his neighbour’s retaining wall gave him an unpleasant surprise, when “going down into my cellar to look, I put my foot in to a great heap of turds, by which I find that Mr Turner’s house of office [cesspit] is full and comes into my cellar which troubles me”[35].

By the 1840s, it was unpleasantly obvious that the sewerage system had widespread and serious problems. The innovation of flush lavatories, while having its own attractions, had actually worsened the situation, as the water had the effect of filling up the cesspools “20 times as fast”, and with liquids, which made them more difficult to clean [36]. There were so many cesspools that the walls between them frequently collapsed, effectively forming “cess lakes”. The overflow liquid contaminated the ground, while the solids slowly seeped into neighbouring cellars and streets, oozing up through the bricks every time it rained. In St Giles, for example, it was reported that “whole areas of the cellars were full of nightsoil to the depth of three feet” and yards were “covered in nightsoil … to the depth of nearly six inches” [37].

Human waste was also being emptied via water draining tunnels into the Thames, with predictable results (Figs 5, 5A)

The issue finally came to a head in the warm summer of 1858. The stench in the Thames from receiving raw sewage, industrial outflows, carcases and other horrors became unbearable. The result, creating what became known as the “Great Stink”, offended even Parliamentary noses [38]. The government finally inaugurated a city-wide sewage building project, and the work of the nightmen started, quite literally, to dry up.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the unappealing aspect of their job, nightmen were generally regarded with some respect. It was a curiously intimate task they performed, one which removed the potential (or actuality) of an unpleasant and embarrassing leakage, or worse. Running a nightman’s business involved organising staff and investing significant capital in the cart, horses and equipment. It was a career that a person of few advantages might even aspire to.

Mayhew recounts how some “better class” chimney sweepers, who had risen to run their own businesses and become settled in a locality, might gradually obtain the trade of the neighborhood; then, as their circumstances improved, they have been able to get horses and carts, and become nightmen [39], often maintaining their side businesses of rubbish carting or chimney sweeping. He goes on to report that there were many nightmen of comparative wealth, as they typically earned a wage that was two to three times the salary of a skilled man. As the contemporary proverb said, “we will bear with the stink if it bring but the chink”. Indeed, it seems that the “smell of gain was fragrant even to night-workers” [40].

In addition, anyone who took obvious offence at the nightman, or the smell of the cart, would be aware that they were in a somewhat vulnerable position. If, as the proverb says, “no man is a hero to his valet”, this applies with extra force to his nightman. It was in all parties’ interests that a clean job was done. And if you objected to the noise or smell, the watchmen might have the obvious rejoinder: “if you would always keep your tails shut, you should not now have occasion to stop your noses” [41].

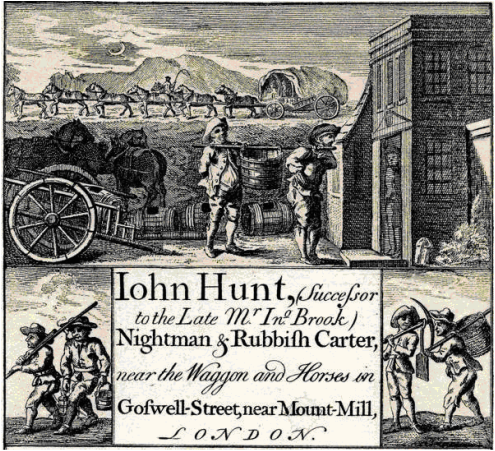

For the nightman, his local reputation was important not just from a personal point of view, but because of the value of maintaining repeat business. Nightmen commonly issued trade cards advertising their business (Fig 6). Elaborate illustrations on the card typically depicted tidily-dressed fellows going about the job in an orderly and respectable manner. Further reflecting the image that they wished to project, the cards typically stressed the discretion, reliability, continuity or family nature of the business. So, for example, John Hunt in Fig 6 notes that he is the successor to the late Mr Brook. In other trade cards, a Richard Harper notes that he has “the care and affiliance of his Son, who is always in the Business”, and a Robert Stone states that the business is “now carried on by his daughter, Mary Burnett”.

Mayhew recounts how some “better class” chimney sweepers, who had risen to run their own businesses and become settled in a locality, might gradually obtain the trade of the neighborhood; then, as their circumstances improved, they have been able to get horses and carts, and become nightmen [39], often maintaining their side businesses of rubbish carting or chimney sweeping. He goes on to report that there were many nightmen of comparative wealth, as they typically earned a wage that was two to three times the salary of a skilled man. As the contemporary proverb said, “we will bear with the stink if it bring but the chink”. Indeed, it seems that the “smell of gain was fragrant even to night-workers” [40].

In addition, anyone who took obvious offence at the nightman, or the smell of the cart, would be aware that they were in a somewhat vulnerable position. If, as the proverb says, “no man is a hero to his valet”, this applies with extra force to his nightman. It was in all parties’ interests that a clean job was done. And if you objected to the noise or smell, the watchmen might have the obvious rejoinder: “if you would always keep your tails shut, you should not now have occasion to stop your noses” [41].

For the nightman, his local reputation was important not just from a personal point of view, but because of the value of maintaining repeat business. Nightmen commonly issued trade cards advertising their business (Fig 6). Elaborate illustrations on the card typically depicted tidily-dressed fellows going about the job in an orderly and respectable manner. Further reflecting the image that they wished to project, the cards typically stressed the discretion, reliability, continuity or family nature of the business. So, for example, John Hunt in Fig 6 notes that he is the successor to the late Mr Brook. In other trade cards, a Richard Harper notes that he has “the care and affiliance of his Son, who is always in the Business”, and a Robert Stone states that the business is “now carried on by his daughter, Mary Burnett”.

Above all, customers were assured that “decency” would be preserved. As one Samuel Foulger says in his trade card, “gentlemen etc may depend of having their business decently performed”. And the ever-present possibility of disastrous situations suddenly arising was tastefully catered for by the assurance that the nightman could work “at the shortest notice on the most reasonable terms”.

The plague corpse bearers

Much more negative emotions – dread, fear and even hatred – were involved with those who carried out our third occupation of the night. These were the corpse bearers of the Great Plague.

The outbreak of the 1664/1665 bubonic plague in London was one of the greatest natural disasters ever to befall the city. The plague, also known as the Black Death [42], was highly infectious, with a high rate of mortality, and with no known cure. Some 70,000 people were recorded as victims over a period of just a few months, accounting for between 15%-20% of the population. Many of those able to do so – possibly up to 40%, including the King – fled the city [43]. Others, including most of the poor, had to take their own chances and stay home in a decreasingly desolated city.

Stringent controls were imposed in the hope of controlling the disease. Typically, these were left to be enforced by the local parishes. So, the parish employed “searchers” – mainly older women – to identify the afflicted and to report their deaths. Once a case was confirmed, the entire household was locked up, and an identifying red cross painted in the door, together with a notification “Lord have mercy on us”. Watchers were appointed to ensure that no members of the household left, whether afflicted or not, and to supervise the passing in of food and other necessary supplies from other members of the community.

The sheer number of victims raised horrific practical problems of dealing with their burial [44]. Traditionally, funerals and burials had, of course, been surrounded by a number of ceremonies, designed to ease the transition and provide some outlet for grieving. This no longer applied. Under the official Plague Orders issued by the Lord Mayor, bodies had to be dealt with summarily, with no funeral procession and no family involvement. As bodies literally mounted up, even individual interments, and coffins, started becoming impractical in many areas. Instead, large pits were dug, where large numbers of bodies – sometimes amounting to a thousand – were, in effect, dumped indiscriminately. The stench and the general horror of the scene was appalling.

Collection of the corpses was permitted only at night. An early experiment of doing it by day had to be abandoned because it induced fear and panic among the public, not to mention the increased risk of infection. The demand became so great, however, that the restriction to night-time collections and burials was not always observed. In his diary, Samuel Pepys recounts how he witnessed “in broad daylight two or three burials upon the [Thames] bankeside, one at the very heels of the other; doubtless all of the plague, and yet at least forty or fifty people going along with every one of them” [45].

While understandable, the night collections also served to increase the ghoulishness of the procedure. This already was bad enough. The procedures for removal of bodies from their deathbeds to these graves must have seemed extraordinarily callous for the family members of the victim. After being locked up for days with the dying loved one, only obtaining access to the outside at night, members in afflicted households would hear the trundling of the “dead-carts” in their street, typically preceded by a “linke” man [46] holding a burning torch and another ringing a warning bell, with the driver calling out “Bring out your dead!”.

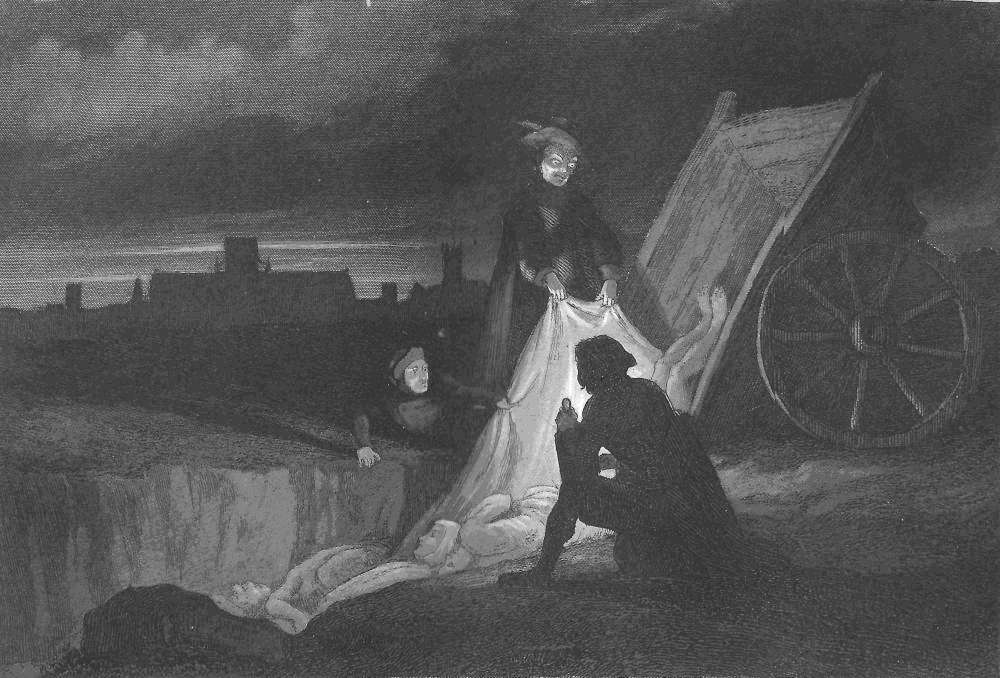

Those inside the afflicted house would call out if there was a body to collect. Sometimes the driver pretended not to hear unless some coins were thrown out. The body was then unceremoniously manhandled, often with the aid of a hook on a long pole into the dead-cart (Fig 7) to join the others already lying there, and trundled off to the grave or pit. It could even happen that persons who were not quite dead, but who had collapsed in the street, were accidentally (or recklessly) included.

The outbreak of the 1664/1665 bubonic plague in London was one of the greatest natural disasters ever to befall the city. The plague, also known as the Black Death [42], was highly infectious, with a high rate of mortality, and with no known cure. Some 70,000 people were recorded as victims over a period of just a few months, accounting for between 15%-20% of the population. Many of those able to do so – possibly up to 40%, including the King – fled the city [43]. Others, including most of the poor, had to take their own chances and stay home in a decreasingly desolated city.

Stringent controls were imposed in the hope of controlling the disease. Typically, these were left to be enforced by the local parishes. So, the parish employed “searchers” – mainly older women – to identify the afflicted and to report their deaths. Once a case was confirmed, the entire household was locked up, and an identifying red cross painted in the door, together with a notification “Lord have mercy on us”. Watchers were appointed to ensure that no members of the household left, whether afflicted or not, and to supervise the passing in of food and other necessary supplies from other members of the community.

The sheer number of victims raised horrific practical problems of dealing with their burial [44]. Traditionally, funerals and burials had, of course, been surrounded by a number of ceremonies, designed to ease the transition and provide some outlet for grieving. This no longer applied. Under the official Plague Orders issued by the Lord Mayor, bodies had to be dealt with summarily, with no funeral procession and no family involvement. As bodies literally mounted up, even individual interments, and coffins, started becoming impractical in many areas. Instead, large pits were dug, where large numbers of bodies – sometimes amounting to a thousand – were, in effect, dumped indiscriminately. The stench and the general horror of the scene was appalling.

Collection of the corpses was permitted only at night. An early experiment of doing it by day had to be abandoned because it induced fear and panic among the public, not to mention the increased risk of infection. The demand became so great, however, that the restriction to night-time collections and burials was not always observed. In his diary, Samuel Pepys recounts how he witnessed “in broad daylight two or three burials upon the [Thames] bankeside, one at the very heels of the other; doubtless all of the plague, and yet at least forty or fifty people going along with every one of them” [45].

While understandable, the night collections also served to increase the ghoulishness of the procedure. This already was bad enough. The procedures for removal of bodies from their deathbeds to these graves must have seemed extraordinarily callous for the family members of the victim. After being locked up for days with the dying loved one, only obtaining access to the outside at night, members in afflicted households would hear the trundling of the “dead-carts” in their street, typically preceded by a “linke” man [46] holding a burning torch and another ringing a warning bell, with the driver calling out “Bring out your dead!”.

Those inside the afflicted house would call out if there was a body to collect. Sometimes the driver pretended not to hear unless some coins were thrown out. The body was then unceremoniously manhandled, often with the aid of a hook on a long pole into the dead-cart (Fig 7) to join the others already lying there, and trundled off to the grave or pit. It could even happen that persons who were not quite dead, but who had collapsed in the street, were accidentally (or recklessly) included.

|

The night-time collections also meant that it was dangerous for anyone else to be out at night, and in fact a curfew forbade this. Pepys, a notorious night-owl, sometimes found himself breaking the curfew, and recounts how he could not get his waterman to go elsewhere at night for fear of the plague, and of his own “great fear of meeting dead corpses” [47].

|

It appears, not surprisingly, that these bearers of the dead were generally regarded with fear and horror. Unfortunately, unlike the nightmen, it appears that they did little to ameliorate their reputation, or even to give it any consideration at all [48]. By most accounts, they were usually rough drunken men, stinking with the effluvia of death, poorly educated, previously virtually unemployable but now earning more than they had ever done before, secure in the knowledge that they were in desperately short supply. They appeared to treat the bodies with little or no respect, and to frequently take what seemed to be a perverted pleasure in the offensive aspects of their job.

Moote describes one “foul-mouthed bearer” who had terrified the poor of Covent Garden and St Martin in the Fields by exposing bodies to the public and offering them as firewood with a mock cry, “Faggots, faggots, five for sixpence” [49]. Defoe, in his novel written some years after the event, describes them as “undaunted creatures” who searched the pockets of the dead and sometimes stripped off their clothes if they were well-dressed, carrying off what they could [50]. This type of reputation appeared to be common in many countries where the plague spread. In Venice, for example, the bearers were referred to as pizzigamorti (“beasts of burial”) and were notorious for their “wickedness and cunning tricks” [51].Many of the bearers had an irrational (and incorrect) view that they themselves were immune from the plague, and almost invariably were smoking pipes in the belief that tobacco smoke was a sort of plague preventative. Smelling constantly of death and decay, they had to be housed away from the public in churchyards, adding to their public perception as almost inhuman, a perception that, not surprisingly, came to be reflected and perpetuated in popular art (Fig 8).

Moote describes one “foul-mouthed bearer” who had terrified the poor of Covent Garden and St Martin in the Fields by exposing bodies to the public and offering them as firewood with a mock cry, “Faggots, faggots, five for sixpence” [49]. Defoe, in his novel written some years after the event, describes them as “undaunted creatures” who searched the pockets of the dead and sometimes stripped off their clothes if they were well-dressed, carrying off what they could [50]. This type of reputation appeared to be common in many countries where the plague spread. In Venice, for example, the bearers were referred to as pizzigamorti (“beasts of burial”) and were notorious for their “wickedness and cunning tricks” [51].Many of the bearers had an irrational (and incorrect) view that they themselves were immune from the plague, and almost invariably were smoking pipes in the belief that tobacco smoke was a sort of plague preventative. Smelling constantly of death and decay, they had to be housed away from the public in churchyards, adding to their public perception as almost inhuman, a perception that, not surprisingly, came to be reflected and perpetuated in popular art (Fig 8).

Conclusion

None of these occupations could be described as attractive propositions today, or even at the time. And, not surprisingly, none of them have survived, other than in radically altered forms. Advances in sanitation, medicine, crime enforcement and industrial practice, plus a changing conception of governmental responsibilities, have combined to physically or emotionally sanitise the functions that they originally served.

These occupations were all carried on at night, and for good – though different – reasons. In the case of the watchmen, this was simply a response to the nature of the job; with nightmen it was a matter of sparing the public’s embarrassment (or sensitive noses), while the night-time corpse-bearing was designed to spare public horror and panic.

It may initially seem surprising that nightmen who were occupied in digging up and disposing of human excreta should be regarded much more favourably, and as more respectable, than the watchmen charged with maintaining public order and security. As we have seen, however, this apparent discrepancy may be explained – at least in part – by the tendency for watchmen to be older, poorer, more corruptible and less physically able than the nightmen, who tended to be more independent, enterprising, richer, more canny and more efficient at the job they were required to do.

This differences were reflected in popular illustrations and writings of the time. However, these illustrators and writers, with their propensity to satirise or strive for comic effect, also went further and played a role in exaggerating those differences. Often too, as we have seen, there was also a tendency to actually distort the situation for political purposes. This cautionary note about the possible shortcomings of art and literature as reliable guides to reality should be remembered whenever one seeks to interpret the past. □

© Philip McCouat 2014, 2018

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

If you enjoyed this article you may also be interested in Surviving the Black Death

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

These occupations were all carried on at night, and for good – though different – reasons. In the case of the watchmen, this was simply a response to the nature of the job; with nightmen it was a matter of sparing the public’s embarrassment (or sensitive noses), while the night-time corpse-bearing was designed to spare public horror and panic.

It may initially seem surprising that nightmen who were occupied in digging up and disposing of human excreta should be regarded much more favourably, and as more respectable, than the watchmen charged with maintaining public order and security. As we have seen, however, this apparent discrepancy may be explained – at least in part – by the tendency for watchmen to be older, poorer, more corruptible and less physically able than the nightmen, who tended to be more independent, enterprising, richer, more canny and more efficient at the job they were required to do.

This differences were reflected in popular illustrations and writings of the time. However, these illustrators and writers, with their propensity to satirise or strive for comic effect, also went further and played a role in exaggerating those differences. Often too, as we have seen, there was also a tendency to actually distort the situation for political purposes. This cautionary note about the possible shortcomings of art and literature as reliable guides to reality should be remembered whenever one seeks to interpret the past. □

© Philip McCouat 2014, 2018

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

If you enjoyed this article you may also be interested in Surviving the Black Death

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

Endnotes

[1] A Roger Ekirch, At Day’s Close: A History of Nighttime, Wiedenfeld and Nicholson, London, 2005, at 75. Incidentally, Rembrandt’s famous painting popularly known as The Night Watch (1642) is something of a misnomer, as it portrays a local private militia force.

[2] Philip Rawlings, Policing: A Short History, Willan Publ, Devon, 2002, at 64.

[3] Numerous versions of this song exist.

[4] Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, entry for 11 September 1663; Ekirch, op cit at 80.

[5] Judith Flanders, The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London, Atlantic Books. London, 2012, at 22.

[6] Ekirch, op cit at 80; Rawlings, op cit at 66.

[7] Dan Cruikshank and Neil Burton, Life in the Georgian City, Viking, London, 1990, at 17; Cesar de Saussure, A Foreign View of England in the Reigns of George I and George II, transl Mme Van Muyden, John Murrray, London, 1902. https://archive.org/details/foreignviewofeng00sausuoft

[8] William Shakespeare, Ado 1598/99, Act III Scene 3.

[9] Emily Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise and Stench in England 1600-1770, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007, at 109.

[10] Henry Fielding, cited in John Briggs and Ors, Crime And Punishment In England: An Introductory History, Routledge, Oxon, 1996, at 55-56.

[11] Ekirch, op cit at 79.

[12] Tobias Smollet, Humphrey Clinker, The New American Library, New York, 1960 (orig publ 1771), at 126.

[13] Robert Southey, Letters from England, ed Jack Simmons, Alan Sutton, Gloucester 1984, p 46, cited in Flanders, op cit at 32.

[14] John Pearson, quoted by David Ascoli, The Queen’s Peace: The Origins and Developnent of the Metropolitan Police 1829-1979, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1979 at 24.

[15] Pierce Egan, Life in London; or, The Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, Esq. and his elegant friend Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, The Oxonian, in their Rambles and Sprees through the Metropolis, Sherwood, Neely and Jones, London, 1821at 268-9.

[16] Henry Mayhew, Mayhew’s London: Being Selections from ‘London Labour and the London Poor’, 1851 at 473, archive.org/stream/mayhewslondonbei00mayhuoft/mayhewslondonbei00mayhuoft_djvu.txt.

[17] Some moves were made. A small detective force for criminal investigation, as distinct from watchman’s duties, had been established by the novelist/magistrate Henry Fielding in 1753. These were known as the “Bow Street Runners”. Professional and often corrupt “thief takers”, essentially bounty hunters, were also active in locating known offenders.

[18] Ekirch, op cit at 80.

[19] Rawlings, op cit at 13.

[20] Ekirch, op cit at 80.

[21] Smollett, op cit at 128.

[22] Ekirch, op cit at 80.

[23] Rawlings, op cit at 113. Despite their replacement in 1829, a few of the old London watch hung on in unexpected places. The Inns of Court had a watchman calling the hours until 1864: Flanders, op cit at 33n.

[24] Ruth Paley”An imperfect, Inadequate and Wretched System? Policing London Before Peel”, Criminal Justice History, X (1989) 95; Phillip Thurmond Smith, Policing Victorian London: Political Policing, Public Order and the Metropolitan Police, Greenwood, Westport, 1985, at 20; Robert D Storch, “The Old English Constabulary”, History Today, 49.11 (Nov 1999) 43.

[25] David Taylor, The New Police in Nineteenth Century England: crime, conflict and control, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1997, at 5, 15.

[26] Cruikshank. op cit at 91-4.

[27] Cockayne, op cit at 143.

[28] Or sometimes women, typically carrying on the business of their father or husband.

[29] Karen Newman, Cultural Capitals: Early Modern London and Paris, Princeton University Press, 2009. at 82. For the connection between the sewage problem and outbreaks of cholera in the city, see Deborah Cadbury, Seven Winders of the Industrial World, Fourth Estate, London, 2003 at 153 ff.

[30] Flanders, op cit at 206-7.

[31] Mayhew, op cit at 351.

[32] Flanders, op cit at 206-7.

[33] Robert Southey, Letters from England, ed Jack Simmons, Alan Sutton, Gloucester 1984, cited in Cruickshank, op cit at 94.

[34] About 3 hectares: Cockayne, op cit at 190-1.

[35] Pepys, op cit, entry for 20 October 1660.

[36] Flanders, op cit at 208.

[37] Flanders, op cit at 206-7. See also Lee Jackson, Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth, Yale University Press, 2014.

[38] See generally Stephen Halliday, The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis, Sutton Publ, Stroud, 2001. [39] Mayhew, op cit at 369.

[40] Cockayne, op cit at 242.

[41] Newman, op cit at 83.

[42] For our account of the earlier outbreak of the Black Death in 14th century Italy, see here.

[43] A Lloyd Moote and Dorothy C Moote, The Great Plague: The Story of London’s Most Deadly Year, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2004, at 11.

[44] See generally Vanessa Harding, “Burial of the plague dead in early modern London”, in Epidemic Disease in London, ed. J.A.I. Champion (Centre for Metropolitan History Working Papers Series, No. 1, 1993): pp. 53-64. [45] Pepys, op cit, entry for 6 September 1665.

[46] Pepys, op cit, entry for 20 August 1665.

[47] Pepys, op cit, entry for 20 August 1665.

[48] James Leasor, The Plague and the Fire, House of Stratus, Cornwall, 2001, at 131-3. [49] Moote, op cit at 225. The offender was severely punished. [50] Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year, Penguin Classics, 1986 (orig publ 1722).

[51] Jane Stevens Crawshaw, “The Beasts of Burial: Pizzigamorti and Public Health for the Plague in Early Modern Venice”, Social History of Medicine, Vol 24, Iss 3, 570.

© Philip McCouat 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

[2] Philip Rawlings, Policing: A Short History, Willan Publ, Devon, 2002, at 64.

[3] Numerous versions of this song exist.

[4] Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, entry for 11 September 1663; Ekirch, op cit at 80.

[5] Judith Flanders, The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London, Atlantic Books. London, 2012, at 22.

[6] Ekirch, op cit at 80; Rawlings, op cit at 66.

[7] Dan Cruikshank and Neil Burton, Life in the Georgian City, Viking, London, 1990, at 17; Cesar de Saussure, A Foreign View of England in the Reigns of George I and George II, transl Mme Van Muyden, John Murrray, London, 1902. https://archive.org/details/foreignviewofeng00sausuoft

[8] William Shakespeare, Ado 1598/99, Act III Scene 3.

[9] Emily Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise and Stench in England 1600-1770, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007, at 109.

[10] Henry Fielding, cited in John Briggs and Ors, Crime And Punishment In England: An Introductory History, Routledge, Oxon, 1996, at 55-56.

[11] Ekirch, op cit at 79.

[12] Tobias Smollet, Humphrey Clinker, The New American Library, New York, 1960 (orig publ 1771), at 126.

[13] Robert Southey, Letters from England, ed Jack Simmons, Alan Sutton, Gloucester 1984, p 46, cited in Flanders, op cit at 32.

[14] John Pearson, quoted by David Ascoli, The Queen’s Peace: The Origins and Developnent of the Metropolitan Police 1829-1979, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1979 at 24.

[15] Pierce Egan, Life in London; or, The Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, Esq. and his elegant friend Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, The Oxonian, in their Rambles and Sprees through the Metropolis, Sherwood, Neely and Jones, London, 1821at 268-9.

[16] Henry Mayhew, Mayhew’s London: Being Selections from ‘London Labour and the London Poor’, 1851 at 473, archive.org/stream/mayhewslondonbei00mayhuoft/mayhewslondonbei00mayhuoft_djvu.txt.

[17] Some moves were made. A small detective force for criminal investigation, as distinct from watchman’s duties, had been established by the novelist/magistrate Henry Fielding in 1753. These were known as the “Bow Street Runners”. Professional and often corrupt “thief takers”, essentially bounty hunters, were also active in locating known offenders.

[18] Ekirch, op cit at 80.

[19] Rawlings, op cit at 13.

[20] Ekirch, op cit at 80.

[21] Smollett, op cit at 128.

[22] Ekirch, op cit at 80.

[23] Rawlings, op cit at 113. Despite their replacement in 1829, a few of the old London watch hung on in unexpected places. The Inns of Court had a watchman calling the hours until 1864: Flanders, op cit at 33n.

[24] Ruth Paley”An imperfect, Inadequate and Wretched System? Policing London Before Peel”, Criminal Justice History, X (1989) 95; Phillip Thurmond Smith, Policing Victorian London: Political Policing, Public Order and the Metropolitan Police, Greenwood, Westport, 1985, at 20; Robert D Storch, “The Old English Constabulary”, History Today, 49.11 (Nov 1999) 43.

[25] David Taylor, The New Police in Nineteenth Century England: crime, conflict and control, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1997, at 5, 15.

[26] Cruikshank. op cit at 91-4.

[27] Cockayne, op cit at 143.

[28] Or sometimes women, typically carrying on the business of their father or husband.

[29] Karen Newman, Cultural Capitals: Early Modern London and Paris, Princeton University Press, 2009. at 82. For the connection between the sewage problem and outbreaks of cholera in the city, see Deborah Cadbury, Seven Winders of the Industrial World, Fourth Estate, London, 2003 at 153 ff.

[30] Flanders, op cit at 206-7.

[31] Mayhew, op cit at 351.

[32] Flanders, op cit at 206-7.

[33] Robert Southey, Letters from England, ed Jack Simmons, Alan Sutton, Gloucester 1984, cited in Cruickshank, op cit at 94.

[34] About 3 hectares: Cockayne, op cit at 190-1.

[35] Pepys, op cit, entry for 20 October 1660.

[36] Flanders, op cit at 208.

[37] Flanders, op cit at 206-7. See also Lee Jackson, Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth, Yale University Press, 2014.

[38] See generally Stephen Halliday, The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis, Sutton Publ, Stroud, 2001. [39] Mayhew, op cit at 369.

[40] Cockayne, op cit at 242.

[41] Newman, op cit at 83.

[42] For our account of the earlier outbreak of the Black Death in 14th century Italy, see here.

[43] A Lloyd Moote and Dorothy C Moote, The Great Plague: The Story of London’s Most Deadly Year, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2004, at 11.

[44] See generally Vanessa Harding, “Burial of the plague dead in early modern London”, in Epidemic Disease in London, ed. J.A.I. Champion (Centre for Metropolitan History Working Papers Series, No. 1, 1993): pp. 53-64. [45] Pepys, op cit, entry for 6 September 1665.

[46] Pepys, op cit, entry for 20 August 1665.

[47] Pepys, op cit, entry for 20 August 1665.

[48] James Leasor, The Plague and the Fire, House of Stratus, Cornwall, 2001, at 131-3. [49] Moote, op cit at 225. The offender was severely punished. [50] Daniel Defoe, A Journal of the Plague Year, Penguin Classics, 1986 (orig publ 1722).

[51] Jane Stevens Crawshaw, “The Beasts of Burial: Pizzigamorti and Public Health for the Plague in Early Modern Venice”, Social History of Medicine, Vol 24, Iss 3, 570.

© Philip McCouat 2014

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME