Michelangelo's disputed Entombment

By Philip McCouat For reader comments on this article see here

In the National Gallery in London there is an extraordinary painting entitled The Entombment (Fig 1). Attributed to Michelangelo, it portrays the crucified Christ being hauled bodily up a flight of stone stairs to his tomb.

The first aspect of the painting that strikes most viewers is the fact that it is unfinished – parts of the painting are not just sketchy, but appear to be virtually blank. But this is just the start of the mysteries that surround this work. Where did it come from? Why is it unfinished? Why do some of the people portrayed in it appear so strange? And is it really by Michelangelo? In this article, we’ll examine just why this painting has raised so many questions, what explanations have been proposed, and what may still remain unresolved.

In the National Gallery in London there is an extraordinary painting entitled The Entombment (Fig 1). Attributed to Michelangelo, it portrays the crucified Christ being hauled bodily up a flight of stone stairs to his tomb.

The first aspect of the painting that strikes most viewers is the fact that it is unfinished – parts of the painting are not just sketchy, but appear to be virtually blank. But this is just the start of the mysteries that surround this work. Where did it come from? Why is it unfinished? Why do some of the people portrayed in it appear so strange? And is it really by Michelangelo? In this article, we’ll examine just why this painting has raised so many questions, what explanations have been proposed, and what may still remain unresolved.

Problems with the cast

Given that the Entombment concerns a seminal event in Christian tradition, it may be surprising to some that there is so much uncertainty about the identities, and even the gender, of some of the characters in the painting.

The central figure is, of course, the slumping Christ, miraculously unwounded. It appears that the kneeling woman in the lower left of the painting, as the viewer sees it, is probably one of the Marys [1], contemplating something in her unfinished right hand [2]. The massively-built bearer on the left is probably St John the Evangelist, characterised by his orange-reddish robe and long hair. The older man at the back is possibly Joseph of Arimathaea, who had given up his own tomb for Christ. The woman on the far right may be Mary Salome, or one of the other Marys. Ironically, the identity of the figure intended for the blank space on the lower right – the most unfinished part of the painting – is among the least contentious, as it is universally accepted as a kneeling Virgin Mary.

Perhaps the most enigmatic figure is the bearer on the right. She (or he) is as tall and elongated as St John is massive, and is commonly identified as yet another of the Marys, typically Mary Magdalene. While it might be thought unlikely that a woman would be given this heavy task, Michael Hirst, a leading authority on Michelangelo, points out that women bearers are conspicuous in Michelangelo’s drawings of a number of Passion scenes [3]. However, in the drawings he cites, the women appear to be only supporting the body, which is rather a different thing from actually carrying it up a flight of steps.

Be that as it may, the bearer looks clearly to be female. Even this modest conclusion, however, has been challenged. The National Gallery itself appears to identify the figure as Nicodemus [4]. Cecil Gould, on the other hand, has claimed that the right bearer is actually St John, and that the left bearer, traditionally identified as that saint, is probably Nicodemus [5]. Gould considers that the undoubted height and broad shoulders of the right bearer indicate that it is a male, and that the hairstyle, which would normally suggest a female to most viewers, is actually shared by some of the male figures (ignudi) on the Sistine ceiling.

The facial expressions, or rather the lack of them, are rather puzzling. While the Mary on the far right looks a little sad, all the others look either neutral, self-absorbed or even a little bored. It is, of course, possible to regard this “marked emotional reticence” (as Hirst describes it [6]), as a virtue rather than a defect, but is does add to the general air of ambiguity.

The central figure is, of course, the slumping Christ, miraculously unwounded. It appears that the kneeling woman in the lower left of the painting, as the viewer sees it, is probably one of the Marys [1], contemplating something in her unfinished right hand [2]. The massively-built bearer on the left is probably St John the Evangelist, characterised by his orange-reddish robe and long hair. The older man at the back is possibly Joseph of Arimathaea, who had given up his own tomb for Christ. The woman on the far right may be Mary Salome, or one of the other Marys. Ironically, the identity of the figure intended for the blank space on the lower right – the most unfinished part of the painting – is among the least contentious, as it is universally accepted as a kneeling Virgin Mary.

Perhaps the most enigmatic figure is the bearer on the right. She (or he) is as tall and elongated as St John is massive, and is commonly identified as yet another of the Marys, typically Mary Magdalene. While it might be thought unlikely that a woman would be given this heavy task, Michael Hirst, a leading authority on Michelangelo, points out that women bearers are conspicuous in Michelangelo’s drawings of a number of Passion scenes [3]. However, in the drawings he cites, the women appear to be only supporting the body, which is rather a different thing from actually carrying it up a flight of steps.

Be that as it may, the bearer looks clearly to be female. Even this modest conclusion, however, has been challenged. The National Gallery itself appears to identify the figure as Nicodemus [4]. Cecil Gould, on the other hand, has claimed that the right bearer is actually St John, and that the left bearer, traditionally identified as that saint, is probably Nicodemus [5]. Gould considers that the undoubted height and broad shoulders of the right bearer indicate that it is a male, and that the hairstyle, which would normally suggest a female to most viewers, is actually shared by some of the male figures (ignudi) on the Sistine ceiling.

The facial expressions, or rather the lack of them, are rather puzzling. While the Mary on the far right looks a little sad, all the others look either neutral, self-absorbed or even a little bored. It is, of course, possible to regard this “marked emotional reticence” (as Hirst describes it [6]), as a virtue rather than a defect, but is does add to the general air of ambiguity.

The composition

The seemingly odd posture of the enigmatic elongated bearer, almost on the verge of tipping over, also gives rise to more significant issues relating to the composition of the work as a whole. This is complicated by the unfinished state of the painting, most notably in the figure’s lack of both a right arm and a leg [7]. However, it is difficult to imagine where these missing limbs could be placed in order to provide a convincing depiction of a person who is holding a sling to carry an extremely heavy load up a flight of stairs. Hirst, among others, while a strong supporter of the painting, concedes that this figure is its “least successful” feature [8].

The depiction of the two bearers – both leaning outwards even though facing in opposite directions – adds to the puzzle. Andrew Graham-Dixon, another enthusiastic supporter of the painting, grants that the posture of the bearers introduces a “somewhat incongruous” elegance to the odd composition, which he agrees is “less than convincing if judged by the criterion of realism”. However, he makes the valuable point that, as an intended altarpiece, the painting is designed as an icon to be looked up at by the kneeling faithful. When viewed from this angle, the “otherwise peculiar perspective” seems to make more sense. The lack of connection between the figures and the earth seems less of a flaw, and assumes more the appearance of a type of Ascension [9]. It has also been suggested that the poses of bearers are linked to classical sculptures of classical heroes [10].

Graham-Dixon nevertheless concedes that the composition is problematic. In fact, he considers that this may be the reason that Michelangelo deliberately decided not to finish the painting. He speculates, fairly boldly, that Michelangelo’s depiction of the central Christ figure was so perfect, with “a delicacy and a strength of feeling beyond description”, that it is “difficult to see how [Michelangelo] could have finished the painting without diluting its concentration on that single, sublime body”. According to Graham-Dixon, “the system of checks and balances which [Michelangelo] presumably intended to contain the other figures has clearly proven ineffective, and he has left off rather than elaborate them into the fatal distractions which they were fast becoming”.

Michelangelo scholar John T Spike also suggests that the defects may be attributable to Michelangelo's inexperience in painting, commenting that "if the picture is indeed [Michelangelo's], it is only in these last moments of immaturity that the disjointed groupings and flat perspective -- as if the artist were torn between sculpture and painting -- are imaginable" [11].

The depiction of the two bearers – both leaning outwards even though facing in opposite directions – adds to the puzzle. Andrew Graham-Dixon, another enthusiastic supporter of the painting, grants that the posture of the bearers introduces a “somewhat incongruous” elegance to the odd composition, which he agrees is “less than convincing if judged by the criterion of realism”. However, he makes the valuable point that, as an intended altarpiece, the painting is designed as an icon to be looked up at by the kneeling faithful. When viewed from this angle, the “otherwise peculiar perspective” seems to make more sense. The lack of connection between the figures and the earth seems less of a flaw, and assumes more the appearance of a type of Ascension [9]. It has also been suggested that the poses of bearers are linked to classical sculptures of classical heroes [10].

Graham-Dixon nevertheless concedes that the composition is problematic. In fact, he considers that this may be the reason that Michelangelo deliberately decided not to finish the painting. He speculates, fairly boldly, that Michelangelo’s depiction of the central Christ figure was so perfect, with “a delicacy and a strength of feeling beyond description”, that it is “difficult to see how [Michelangelo] could have finished the painting without diluting its concentration on that single, sublime body”. According to Graham-Dixon, “the system of checks and balances which [Michelangelo] presumably intended to contain the other figures has clearly proven ineffective, and he has left off rather than elaborate them into the fatal distractions which they were fast becoming”.

Michelangelo scholar John T Spike also suggests that the defects may be attributable to Michelangelo's inexperience in painting, commenting that "if the picture is indeed [Michelangelo's], it is only in these last moments of immaturity that the disjointed groupings and flat perspective -- as if the artist were torn between sculpture and painting -- are imaginable" [11].

Colour effects and balance

The colour scheme of the painting is also quite disconcerting. It is hard to ignore St John’s extraordinarily vivid robe; indeed it has been described as “nearly fluorescent” [12]. This stark contrast with the drab olive or brown of the women’s robes, in conjunction with the unfinished state of the painting, contributes to the impression of a rather unreal lack of balance. Thankfully, however, this may be readily explained by the idiosyncratic deterioration of the paint pigments. Jill Dunkerton, after a particularly detailed examination, notes that over the centuries most of the colours have altered to such an extent that “we are left with an entirely false view of the appearance of the painting”[13]. This, rather than any aberration by the artist, is why St John’s robe now appears “obtrusively bright”, and why the “once brilliant green” of the robe of the right bearer has become “sadly discoloured”.

Dunkerton also observes that the darkening of patches in St John’s robe over time has produced “a misplaced depth of tone with sometimes unfortunate results”. Presumably this goes some way to explain the curious impression left with many viewers that St John has somehow been endowed with girlish breasts.

Dunkerton also observes that the darkening of patches in St John’s robe over time has produced “a misplaced depth of tone with sometimes unfortunate results”. Presumably this goes some way to explain the curious impression left with many viewers that St John has somehow been endowed with girlish breasts.

The origins of the Entombment

For many years, very little was known about the origin of the London Entombment. However, one clue was provided by some documentary evidence discovered in 1971. From this, we know that in 1500 Michelangelo was paid to paint a panel for the church of Sant’Agostino in Rome [14]. We also know that Michelangelo did not deliver any such painting, and that he later paid back the full commission price. It is this unfulfilled commission which, it has been claimed, is the unfinished Entombment now held by the National Gallery.

Rather frustratingly, the documentary evidence of the commission does not specify the subject matter of the painting. It is therefore possible that the commission was not for an Entombment at all. We also do not know whether Michelangelo even started work on the commission, though there were apparently no rival projects we know of which would have diverted him from commencing [15]. So, the documentary link between the commission and the London Entombment, while certainly plausible, is nevertheless quite tenuous when considered in isolation.

There are, however, a number of other, more indirect, pieces of evidence that point in one direction or the other. As corroboration, for example, research has indicated that the dimensions, general type of subject matter and left-to-right lighting of the London work are all consistent with the chapel for which the commissioned work was evidently intended [16].

On the other hand, it seems odd that, if Michelangelo did in fact spend six months or so of his life producing a painting such as the London Entombment, he never subsequently referred to it. Nor was it mentioned by any of his contemporaries, nor in any biographies [17]. The painting also does not appear in the detailed inventory of works in Michelangelo’s house drawn up after his death, even though this does refer to other unfinished works of his [18]. Furthermore, acceptance that the unfulfilled commission and the London Entombment are one and the same necessitates a dating of 1500-01, which is a number of years earlier than many observers had previously considered likely [19]. Considered together, these factors create at least some doubts as to the claimed link between the commission and the London painting.

Various works have been also put forward as possible preparatory studies for the painting. If these are by Michelangelo, precede the painting and can legitimately be linked to it, this would provide some corroborative evidence for Michelangelo’s authorship of the painting. Hirst suggests, for example, that a male nude study, currently in the Louvre can “with every probability” be connected with the figure of St John in the painting [20]. However, there are clearly crucial differences – the model is leaning forwards, instead of backwards (as he would presumably need to be in order to carry someone upstairs backwards); his bent right arm, a focal point in the study, is not present at all in the painted St John; and the model is presumably pulling something on his right side, not on his left.

Hirst seeks to partly answer objections such as these by adopting the suggestion that the study was made at a stage in the planning process when Michelangelo was considering placing the male figure on our right of the dead Christ rather than on the left, as finally adopted [21]. However, the most that one can say is that the model’s legs are approximately a mirror image of St John’s, and that the model’s left arm is very approximately in the same position. This seems a long way from being conclusive. It is also interesting that the website of the Louvre, where the drawing is held, states that the drawing is “characteristic of the years 1505/6”, which of course is five years after the commission. It also notes that while “some historians have tried to establish a link” with the London Entombment, the drawing “cannot be connected to any known project of Michelangelo”[22]. On balance, it would appear that although the drawing is probably by Michelangelo, its connection to the Entombment is not established.

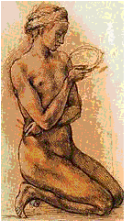

Another Louvre drawing has also been suggested as a study for the kneeling female figure on the left of the painting (Fig 2). This claim is on more certain ground. Certainly, the model’s pose is almost identical to the figure in the painting (though her legs are positioned rather differently). Additionally, there is a link to a post-Crucifixion subject matter, as the girl is contemplating a crown of thorns that she is holding in her right hand, and may be holding nails from the Cross in the other hand [23].

Rather frustratingly, the documentary evidence of the commission does not specify the subject matter of the painting. It is therefore possible that the commission was not for an Entombment at all. We also do not know whether Michelangelo even started work on the commission, though there were apparently no rival projects we know of which would have diverted him from commencing [15]. So, the documentary link between the commission and the London Entombment, while certainly plausible, is nevertheless quite tenuous when considered in isolation.

There are, however, a number of other, more indirect, pieces of evidence that point in one direction or the other. As corroboration, for example, research has indicated that the dimensions, general type of subject matter and left-to-right lighting of the London work are all consistent with the chapel for which the commissioned work was evidently intended [16].

On the other hand, it seems odd that, if Michelangelo did in fact spend six months or so of his life producing a painting such as the London Entombment, he never subsequently referred to it. Nor was it mentioned by any of his contemporaries, nor in any biographies [17]. The painting also does not appear in the detailed inventory of works in Michelangelo’s house drawn up after his death, even though this does refer to other unfinished works of his [18]. Furthermore, acceptance that the unfulfilled commission and the London Entombment are one and the same necessitates a dating of 1500-01, which is a number of years earlier than many observers had previously considered likely [19]. Considered together, these factors create at least some doubts as to the claimed link between the commission and the London painting.

Various works have been also put forward as possible preparatory studies for the painting. If these are by Michelangelo, precede the painting and can legitimately be linked to it, this would provide some corroborative evidence for Michelangelo’s authorship of the painting. Hirst suggests, for example, that a male nude study, currently in the Louvre can “with every probability” be connected with the figure of St John in the painting [20]. However, there are clearly crucial differences – the model is leaning forwards, instead of backwards (as he would presumably need to be in order to carry someone upstairs backwards); his bent right arm, a focal point in the study, is not present at all in the painted St John; and the model is presumably pulling something on his right side, not on his left.

Hirst seeks to partly answer objections such as these by adopting the suggestion that the study was made at a stage in the planning process when Michelangelo was considering placing the male figure on our right of the dead Christ rather than on the left, as finally adopted [21]. However, the most that one can say is that the model’s legs are approximately a mirror image of St John’s, and that the model’s left arm is very approximately in the same position. This seems a long way from being conclusive. It is also interesting that the website of the Louvre, where the drawing is held, states that the drawing is “characteristic of the years 1505/6”, which of course is five years after the commission. It also notes that while “some historians have tried to establish a link” with the London Entombment, the drawing “cannot be connected to any known project of Michelangelo”[22]. On balance, it would appear that although the drawing is probably by Michelangelo, its connection to the Entombment is not established.

Another Louvre drawing has also been suggested as a study for the kneeling female figure on the left of the painting (Fig 2). This claim is on more certain ground. Certainly, the model’s pose is almost identical to the figure in the painting (though her legs are positioned rather differently). Additionally, there is a link to a post-Crucifixion subject matter, as the girl is contemplating a crown of thorns that she is holding in her right hand, and may be holding nails from the Cross in the other hand [23].

|

However, here again there are reasons for doubt. Although supposedly done within a few weeks of the male nude study, which is generally accepted as being by Michelangelo, the kneeling girl study is stylistically so different as to suggest the two studies could be by different hands.

Hirst agrees that the male study is executed with “greater assurance” and “much greater freedom” than the female study, which he says indicates that it was done earlier in the design process [24]. |

This does not seem to be a very conclusive explanation, as the female study also contains has a number of non-Michelangelo elements. For example, the use of a nude girl life model is almost unprecedented; the pinkish colouration is unusual for Michelangelo; and the existence of pen strokes indicating the ground is, as Hirst agrees, a rare feature for Michelangelo’s life studies.

Despite these features, the Louvre itself attributes the drawing to Michelangelo, though noting that certain historians have disputed this [25]. The Louvre’s reasoning appears to be influenced by its belief that, as the drawing is clearly a preparatory study for the Entombment, which it accepts as a Michelangelo, the drawing must also be by Michelangelo. This symbiotic relationship between the drawing and the painting is intriguing – each is used as a corroborative prop for the other. However the inevitability of this relationship may be questioned. Even if the drawing is by Michelangelo, this does not necessarily mean that the painting is also by him. As Gould has pointed out, there is abundant contemporary evidence (mainly in Vasari) that pictures were painted from Michelangelo’s designs, or on the basis of his sketches, by other artists during his lifetime [26].

Despite these features, the Louvre itself attributes the drawing to Michelangelo, though noting that certain historians have disputed this [25]. The Louvre’s reasoning appears to be influenced by its belief that, as the drawing is clearly a preparatory study for the Entombment, which it accepts as a Michelangelo, the drawing must also be by Michelangelo. This symbiotic relationship between the drawing and the painting is intriguing – each is used as a corroborative prop for the other. However the inevitability of this relationship may be questioned. Even if the drawing is by Michelangelo, this does not necessarily mean that the painting is also by him. As Gould has pointed out, there is abundant contemporary evidence (mainly in Vasari) that pictures were painted from Michelangelo’s designs, or on the basis of his sketches, by other artists during his lifetime [26].

Later history and provenance

We have already mentioned that none of Michelangelo’s contemporaries appear to have referred to any unfinished Entombment by him. Indeed, it seems that this virtual cone of silence existed for a period of almost 150 years. The first recorded mention if the painting does not occur until 1644 (or 1649), when an inventory of the prestigious Farnese collection lists a painting by the hand of Michelangelo, portraying Christ being conveyed to his tomb by Mary, St James and Simon of Cyrene [27]. This generally accords with the details of the London Entombment. Hirst notes that the inventory’s attribution to Michelangelo is unhesitating and unequivocal [28]. However, it should be noted that, while this listing provides a valuable possible link to the London Entombment, it actually does not in itself provide any necessary link at all back to the unfulfilled commission, apart from the fact that both works are claimed to be attributable to Michelangelo.

A few years after this, a further inventory of Farnese possessions identifies the painting as unfinished (non finito), but, perhaps significantly, it is now only “said to be” by Michelangelo (si dice esser di Michel’Angelo) [29]. At some stage, the painting evidently passes to Cardinal Fesch and was subsequently disposed of from the Fesch Collection as part of a “throw out” (ausschuss) [30]. It was then purchased in 1846 by Robert Macpherson, a Scottish photographer, painter and sometime dealer.

The circumstances of this fortunate purchase are obscure, and the only known accounts of it vary. Graham-Dixon reports that, according to Macpherson’s friend James Freeman, Macpherson accidentally came across the painting when he was looking through a job lot of pictures which had been sold cheaply at auction. Freeman continues, “Mac had carefully observed among these paintings a large panel over which dust, varnish and smoke had accumulated to such a degree as to make it difficult to distinguish what it represented. There was, however, something in its obscured outlines which made an impression on him, and haunted his recollections of it. Knowing the dealer who had bought the pictures, he went a few weeks later to his shop, and, while looking at some other things, asked carelessly, 'What is that old dark panel there?' 'Oh, that,' replied the dealer, 'is good for nothing, beyond the wood on which the daub is painted. I am going to sell it to a cabinet-maker who wants to make tables out of it’”. Macpherson bought it for a little more than a pound, and smuggled it out of the country [31].

An even more exotic version of this episode, apparently written much later in about 1897, claims that Macpherson saw the picture in a Roman market being used as “a stall or table, used sometimes for fish, frogs, etc but usually old pans, grid-irons, locks, horseshoes etc. He saw that the surface of the barrow looked like a good picture and in order to distract attention from his real purpose he pretended to be drunk and purchased the whole stall and contents for a very small sum” [32].

Wherever the truth lies, it is clear that prior to Macpherson’s purchase, the painting had reached the lowest point in its fortunes. This, however, was soon to change radically. In 1868, Macpherson succeeded in selling the painting to the National Gallery for the sum of £2,000.

A few years after this, a further inventory of Farnese possessions identifies the painting as unfinished (non finito), but, perhaps significantly, it is now only “said to be” by Michelangelo (si dice esser di Michel’Angelo) [29]. At some stage, the painting evidently passes to Cardinal Fesch and was subsequently disposed of from the Fesch Collection as part of a “throw out” (ausschuss) [30]. It was then purchased in 1846 by Robert Macpherson, a Scottish photographer, painter and sometime dealer.

The circumstances of this fortunate purchase are obscure, and the only known accounts of it vary. Graham-Dixon reports that, according to Macpherson’s friend James Freeman, Macpherson accidentally came across the painting when he was looking through a job lot of pictures which had been sold cheaply at auction. Freeman continues, “Mac had carefully observed among these paintings a large panel over which dust, varnish and smoke had accumulated to such a degree as to make it difficult to distinguish what it represented. There was, however, something in its obscured outlines which made an impression on him, and haunted his recollections of it. Knowing the dealer who had bought the pictures, he went a few weeks later to his shop, and, while looking at some other things, asked carelessly, 'What is that old dark panel there?' 'Oh, that,' replied the dealer, 'is good for nothing, beyond the wood on which the daub is painted. I am going to sell it to a cabinet-maker who wants to make tables out of it’”. Macpherson bought it for a little more than a pound, and smuggled it out of the country [31].

An even more exotic version of this episode, apparently written much later in about 1897, claims that Macpherson saw the picture in a Roman market being used as “a stall or table, used sometimes for fish, frogs, etc but usually old pans, grid-irons, locks, horseshoes etc. He saw that the surface of the barrow looked like a good picture and in order to distract attention from his real purpose he pretended to be drunk and purchased the whole stall and contents for a very small sum” [32].

Wherever the truth lies, it is clear that prior to Macpherson’s purchase, the painting had reached the lowest point in its fortunes. This, however, was soon to change radically. In 1868, Macpherson succeeded in selling the painting to the National Gallery for the sum of £2,000.

Evaluation of provenance

What then do we conclude from this complex trail about the provenance of the London Entombment? Hirst concludes that the painting’s whereabouts “between the moment when Michelangelo broke off work on it in the spring of 1501 and its seventeenth century citation in the Farnese collection remain the one obscure episode in its history” [33]. Remember that Hirst is talking here about a period of almost 150 years in which a work supposedly by Michelangelo, one of the most famous painters of the time, lay neglected and completely unrecorded. Even if this were the only gap, it seems an uncomfortably big one.

Furthermore, the claim that this is the only obscure episode in the painting’s history is open to question. What do we make of the circumstances of the acquisition by Macpherson, which Dunkerton describes as an “extraordinary episode” for which the only two documentary sources are in conflict? [34]. It seems that we have no explanation of how a painting attributed to Michelangelo in a prestigious collection could degenerate into an anonymous, neglected, grimy panel that a part-time dealer such as Macpherson could pick out of job lot for a pittance. This would seem to qualify as an extraordinarily obscure episode.

Pursuing this issue further, what could explain this dramatic fall from grace? Is it a possible scenario that doubts had arisen about Michelangelo’s authorship? Is this why, by 1697, the Farnese inventory entry, instead of “unhesitatingly” attributing it to Michelangelo (in Hirst’s words), now said it was only “said to be” by him? Is it why the Fesch Collection included it in a “throw out” sale, ultimately resulting in the picture being purchased by Macpherson? If this is what happened, its more recent reincarnation as a “well-nigh certain” Michelangelo [35] is exquisitely ironic.

However, if it were the case that Michelangelo did not paint the Entombment, this raises the obvious question – who did? Over the years, various possibilities have been proposed with varying degrees of conviction. These alternatives, conveniently summarised by Gould [36], include other specific artists, or assistants or followers of Michelangelo. One of the more intriguing of these is Baccio Bandinelli, a contemporary and apparently almost obsessive admirer of Michelangelo. Bandinelli was primarily a sculptor, quite successful during his lifetime but often maligned by comparison with his more illustrious and more talented rival. He was first suggested in a letter to The Times by JC Robinson as far back as 1881[37], and this claim was revived in 1994, rather provocatively, by Michael Daley [38]. Bandinelli evidently did in fact fail to complete a very similarly described commission, described by Vasari as “an altarpiece of considerable size” which apparently was to include “a dead Christ surrounded by the Maries, with Nicodemus and other figures” [39]. However, it would seem that a much more fully reasoned analysis would be required for a Bandinelli attribution to be convincing in its own right.

Furthermore, the claim that this is the only obscure episode in the painting’s history is open to question. What do we make of the circumstances of the acquisition by Macpherson, which Dunkerton describes as an “extraordinary episode” for which the only two documentary sources are in conflict? [34]. It seems that we have no explanation of how a painting attributed to Michelangelo in a prestigious collection could degenerate into an anonymous, neglected, grimy panel that a part-time dealer such as Macpherson could pick out of job lot for a pittance. This would seem to qualify as an extraordinarily obscure episode.

Pursuing this issue further, what could explain this dramatic fall from grace? Is it a possible scenario that doubts had arisen about Michelangelo’s authorship? Is this why, by 1697, the Farnese inventory entry, instead of “unhesitatingly” attributing it to Michelangelo (in Hirst’s words), now said it was only “said to be” by him? Is it why the Fesch Collection included it in a “throw out” sale, ultimately resulting in the picture being purchased by Macpherson? If this is what happened, its more recent reincarnation as a “well-nigh certain” Michelangelo [35] is exquisitely ironic.

However, if it were the case that Michelangelo did not paint the Entombment, this raises the obvious question – who did? Over the years, various possibilities have been proposed with varying degrees of conviction. These alternatives, conveniently summarised by Gould [36], include other specific artists, or assistants or followers of Michelangelo. One of the more intriguing of these is Baccio Bandinelli, a contemporary and apparently almost obsessive admirer of Michelangelo. Bandinelli was primarily a sculptor, quite successful during his lifetime but often maligned by comparison with his more illustrious and more talented rival. He was first suggested in a letter to The Times by JC Robinson as far back as 1881[37], and this claim was revived in 1994, rather provocatively, by Michael Daley [38]. Bandinelli evidently did in fact fail to complete a very similarly described commission, described by Vasari as “an altarpiece of considerable size” which apparently was to include “a dead Christ surrounded by the Maries, with Nicodemus and other figures” [39]. However, it would seem that a much more fully reasoned analysis would be required for a Bandinelli attribution to be convincing in its own right.

Why is it unfinished?

Irrespective of who painted the London Entombment, the question arises as to why it was not finished. The short answer is that no-one knows for sure. We have already mentioned Graham-Dixon’s speculation that the artist (whom he considers is Michelangelo) deliberately did not finish it because he felt that the completion of the problematic composition would mar the perfection of the painted Christ figure. Of course, a less charitably-minded observer may simply believe that the artist failed to finish for the usual reasons shared by lesser mortals – either they had messed the whole thing up, lost interest, realised it was beyond them, were distracted by other urgent issues, received a better offer, or just ran out of time.

It has also been suggested that many of the unfinished parts of the painting, such as the cloak of the missing Virgin, would have required quantities of the expensive lapis lazuli blue. If this was in short supply, it could be that this would have held up completion of the painting [40]. However, even if this is so, it is difficult to see why the artist could not have completed many other parts of the painting that would not have required blue – an obvious example would be the right arm of the kneeling girl, for whom a study had already been made [41].

If we focus on the particular circumstances of Michelangelo, the answer may simply be that he was forced (or voluntarily decided) to abandon the painting because he needed to leave Rome for Florence in order to procure a highly-prized block of marble that had become available -- a block that he would later use to create his David [42]. John T Spike alternatively suggests that the abandonment of the painting was encouraged, if not occasioned, by the opportunity to carve marble sculptures for the Piccolomini altar in the cathedral of Siena [43].

Certainly, the motivation for the abandonment of the painting must have been pressing. Michelangelo's act in refunding the commission on moneys seems odd, considering that he was so close to finishing the work [44].

It has also been suggested that many of the unfinished parts of the painting, such as the cloak of the missing Virgin, would have required quantities of the expensive lapis lazuli blue. If this was in short supply, it could be that this would have held up completion of the painting [40]. However, even if this is so, it is difficult to see why the artist could not have completed many other parts of the painting that would not have required blue – an obvious example would be the right arm of the kneeling girl, for whom a study had already been made [41].

If we focus on the particular circumstances of Michelangelo, the answer may simply be that he was forced (or voluntarily decided) to abandon the painting because he needed to leave Rome for Florence in order to procure a highly-prized block of marble that had become available -- a block that he would later use to create his David [42]. John T Spike alternatively suggests that the abandonment of the painting was encouraged, if not occasioned, by the opportunity to carve marble sculptures for the Piccolomini altar in the cathedral of Siena [43].

Certainly, the motivation for the abandonment of the painting must have been pressing. Michelangelo's act in refunding the commission on moneys seems odd, considering that he was so close to finishing the work [44].

Conclusion

On balance, the identification of the London Entombment with Michelangelo’s unfulfilled commission of 1500/01 fits with most of the facts and is certainly plausible. However, some puzzling aspects remain, which perhaps prevent us from unqualifiedly accepting Hirst’s conclusion that the identification is “well-nigh certain”.

The reason for this qualification is that all of these puzzling aspects are consistent with an alternative hypothesis. If, say, one assumes that both the kneeling girl study and the painting were done by a talented though lesser artist, then a number of things fall into place. The curious stylistic discrepancy between the kneeling girl study and Michelangelo’s sketch of the nude man is explained. So is the rather awkward composition of the painting, and the fact that neither Michelangelo nor any of his early biographers ever refer to it. This hypothesis also provides a possible explanation of the painting’s dramatic fall from grace which, by 1846, led to it being treated as virtual junk.

Of course, as has already been pointed out, this hypothesis lacks a crucial element, namely a convincing non-Michelangelo identification of the artist of both the kneeling girl and the painting. In the absence of this, the attribution to Michelangelo may need to be considered the more likely, if only by default.

Finally, an obvious point, but one which still needs to be made. Does it really matter whether or not the painting is by Michelangelo? Clearly, resolution of the issue one way or the other might clear up curiosity about some minor aspects of Michelangelo’s artistic journey. It would drastically affect the market value of the work. And it would also affect the reputations of some experts – in some cases quite dramatically – and of the National Gallery itself. However, even though these concerns may be crucial to the professional art world, it is questionable whether they should be central to a viewer’s appreciation of the painting itself, or to any evaluation of its "intrinsic" merits. Perhaps, in the end, the whole exercise may be justified by nothing more than the simple human desire to know – the undeniable element of intellectual excitement in the hunt for a resolution.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2020

We welcome your comments on this article

The reason for this qualification is that all of these puzzling aspects are consistent with an alternative hypothesis. If, say, one assumes that both the kneeling girl study and the painting were done by a talented though lesser artist, then a number of things fall into place. The curious stylistic discrepancy between the kneeling girl study and Michelangelo’s sketch of the nude man is explained. So is the rather awkward composition of the painting, and the fact that neither Michelangelo nor any of his early biographers ever refer to it. This hypothesis also provides a possible explanation of the painting’s dramatic fall from grace which, by 1846, led to it being treated as virtual junk.

Of course, as has already been pointed out, this hypothesis lacks a crucial element, namely a convincing non-Michelangelo identification of the artist of both the kneeling girl and the painting. In the absence of this, the attribution to Michelangelo may need to be considered the more likely, if only by default.

Finally, an obvious point, but one which still needs to be made. Does it really matter whether or not the painting is by Michelangelo? Clearly, resolution of the issue one way or the other might clear up curiosity about some minor aspects of Michelangelo’s artistic journey. It would drastically affect the market value of the work. And it would also affect the reputations of some experts – in some cases quite dramatically – and of the National Gallery itself. However, even though these concerns may be crucial to the professional art world, it is questionable whether they should be central to a viewer’s appreciation of the painting itself, or to any evaluation of its "intrinsic" merits. Perhaps, in the end, the whole exercise may be justified by nothing more than the simple human desire to know – the undeniable element of intellectual excitement in the hunt for a resolution.

© Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2020

We welcome your comments on this article

End notes

1. By tradition, three women who may have been present at Christ’s tomb were Mary Magdalene, Mary Salome, and Mary, the mother of James.

2. The identity and significance of the object is considered later in this article.

3. Hirst, M, and Dunkerton, J, Making and Meaning: The Young Michelangelo, National Gallery Publications Ltd, London, 1994 at 67.

4. Website of National Gallery, London http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/michelangelo-the-entombment (Accessed May 2012).

5. Gould, C, “Michelangelo’s ‘Entombment’: A Further Addendum”, The Burlington Magazine, Vol 116, No 850 (Jan 1974), 31.

6. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 63.

7. The way in which the blank space reserved for the painting of the tomb projects incongruously from the back of the bearer’s head also does not help.

8. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 69.

9. Graham-Dixon, A, “Anatomy of a Genius”, The Independent, 25 October 1994.

10. Hurst and Dunkerton, op cit at 80-81.

11. John T Spike, Young Michelangelo: The Path to the Sistine, Duckworth Overlook, London & New York, 2010, at 132

12. Finlay, V, Colour: Travels through the Paintbox, Folio Society, London 2009, at 265.

13. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 119 – 120.

14. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 57 and works there cited.

15. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 58. Hirst has also noted “that so intimate an associate as Jacopo Gallo was involved would encourage the belief that the artist began work on it” (Hirst, M, Michelangelo, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2011, vol 1 at 40). However, if this is so, it seems even odder that the artist would not finish the work..

16. Nagel, A, “Michelangelo’s London ‘Entombment’ and the Church of S. Agostino in Rome”, The Burlington Magazine, vol 136, No 1092 (Mar 1994), 164.

17. It is not mentioned in Vasari’s detailed 127 page account of his Michelangelo’s life and works (Vasari, G, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, Vol 2. Everyman’s Library, London,1996, at 642-769). The omission is interesting, as Vasari does recount in detail how Baccio Bandinelli failed to complete a very similar commission (at 277). However, it appears that Vasari did not know much about Michelangelo’s early years in any event.

18. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 80 note 27.

19. Gould for example, had considered that the work was first started in 1506 (Gould (1974), op cit at 32). Berenson had dated it c 1504.

20. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit, at 69.

21. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 69.

22. Website of Louvre Museum: http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/male-nude-seen-front (Accessed May 2012)

23. Both of these details in the drawing are in an area of the painting that is unfinished.

24. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 69; Hirst (1986), op cit at 64.

25. Website of Louvre Museum: http://cartelen.louvre.fr/cartelen/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=18341 (Accessed May 2012). For a vigorously sceptical view of the attribution to Michelangelo, see James Beck, book review of Florentine Drawings at the Time of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Renaissance Quarterly, Vol 49, No 2, 445.

26. Gould, C, The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, London, 1962, at 99.

27. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 60. Presumably, Simon of Cyrene is the figure in the painting now generally identified as Joseph of Arimathaea. Simon is traditionally identified as the person who helped Christ carry the cross to Calvary..

28. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 60; Hirst (2011), op cit at 40.

29. Gould, C, “The Provenance of the National Gallery ‘Entombment’ and an early sketch copy”, The Burlington Magazine, Vol 93, No 582 (Sept 1951) 281. These later inventories date from 1653 and 1697. The sketch copy referred to in Gould’s article is undated, but is stated by Hirst to be “probably 17th or 18th century”, which seems to cover most bases (Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 66).

30. Gould (1951), op cit at 281.

31. Graham-Dixon, op cit. The quotations are evidently drawn from Freeman, J, Gatherings from an Artist's Portfolio in Rome, Vol. 2, Roberts Brothers, Boston,1883.

32. Gould (1951), op cit at 281, citing The Early Life of Clement Burlison, Artist, Being his own record of the years 1810 to 1847.

33. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 60, emphasis added.

34. Hirst and Dunkerton, at 131 note 11.

35. Hirst (2011) at 40.

36. Gould (1962), op cit at 94-95. Many of these alternative attributions must now of course be read subject to the qualification that they were made before the discovery of the various pieces of supporting documentation that have been brought to light in the last few decades.

37. Robinson was Superintendent of the Art Collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum and later surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures.

38. Daley, M, “No anatomical logic in Michelangelo’s defence”, The Independent 29 Sept 1994; “Michelangelo’s The Entombment: a cuckoo in the National’s nest”, Art Review, Oct 1994.

39. Vasari, op cit at 277.

40. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 70 and 123 Alternatively, it has been suggested that as the blue was so expensive, Michelangelo may have been waiting for it to be supplied by his patron (Finlay, op cit at 266, citing Langmuir, E, National Gallery Companion Guide, National Gallery Publications, 1994).

41. Dunkerton in Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 116. Overall, Dunkerton considers that the order in which the painting has been left unfinished often seems “inexplicably random” (at 113).

42. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 71.

43. Spike, op cit, at 133.

44. Rab Hatfield, The Wealth of Michelangelo, Editioni di Storia e Letteratura, Rome 2002, cited in Spike, op cit at 132.

© Copyright Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2020

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Michelangelo's disputed Entombment", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to HOME

2. The identity and significance of the object is considered later in this article.

3. Hirst, M, and Dunkerton, J, Making and Meaning: The Young Michelangelo, National Gallery Publications Ltd, London, 1994 at 67.

4. Website of National Gallery, London http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/michelangelo-the-entombment (Accessed May 2012).

5. Gould, C, “Michelangelo’s ‘Entombment’: A Further Addendum”, The Burlington Magazine, Vol 116, No 850 (Jan 1974), 31.

6. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 63.

7. The way in which the blank space reserved for the painting of the tomb projects incongruously from the back of the bearer’s head also does not help.

8. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 69.

9. Graham-Dixon, A, “Anatomy of a Genius”, The Independent, 25 October 1994.

10. Hurst and Dunkerton, op cit at 80-81.

11. John T Spike, Young Michelangelo: The Path to the Sistine, Duckworth Overlook, London & New York, 2010, at 132

12. Finlay, V, Colour: Travels through the Paintbox, Folio Society, London 2009, at 265.

13. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 119 – 120.

14. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 57 and works there cited.

15. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 58. Hirst has also noted “that so intimate an associate as Jacopo Gallo was involved would encourage the belief that the artist began work on it” (Hirst, M, Michelangelo, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2011, vol 1 at 40). However, if this is so, it seems even odder that the artist would not finish the work..

16. Nagel, A, “Michelangelo’s London ‘Entombment’ and the Church of S. Agostino in Rome”, The Burlington Magazine, vol 136, No 1092 (Mar 1994), 164.

17. It is not mentioned in Vasari’s detailed 127 page account of his Michelangelo’s life and works (Vasari, G, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, Vol 2. Everyman’s Library, London,1996, at 642-769). The omission is interesting, as Vasari does recount in detail how Baccio Bandinelli failed to complete a very similar commission (at 277). However, it appears that Vasari did not know much about Michelangelo’s early years in any event.

18. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 80 note 27.

19. Gould for example, had considered that the work was first started in 1506 (Gould (1974), op cit at 32). Berenson had dated it c 1504.

20. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit, at 69.

21. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 69.

22. Website of Louvre Museum: http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/male-nude-seen-front (Accessed May 2012)

23. Both of these details in the drawing are in an area of the painting that is unfinished.

24. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 69; Hirst (1986), op cit at 64.

25. Website of Louvre Museum: http://cartelen.louvre.fr/cartelen/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=18341 (Accessed May 2012). For a vigorously sceptical view of the attribution to Michelangelo, see James Beck, book review of Florentine Drawings at the Time of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Renaissance Quarterly, Vol 49, No 2, 445.

26. Gould, C, The Sixteenth Century Italian Schools, National Gallery Catalogues, London, 1962, at 99.

27. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 60. Presumably, Simon of Cyrene is the figure in the painting now generally identified as Joseph of Arimathaea. Simon is traditionally identified as the person who helped Christ carry the cross to Calvary..

28. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 60; Hirst (2011), op cit at 40.

29. Gould, C, “The Provenance of the National Gallery ‘Entombment’ and an early sketch copy”, The Burlington Magazine, Vol 93, No 582 (Sept 1951) 281. These later inventories date from 1653 and 1697. The sketch copy referred to in Gould’s article is undated, but is stated by Hirst to be “probably 17th or 18th century”, which seems to cover most bases (Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 66).

30. Gould (1951), op cit at 281.

31. Graham-Dixon, op cit. The quotations are evidently drawn from Freeman, J, Gatherings from an Artist's Portfolio in Rome, Vol. 2, Roberts Brothers, Boston,1883.

32. Gould (1951), op cit at 281, citing The Early Life of Clement Burlison, Artist, Being his own record of the years 1810 to 1847.

33. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 60, emphasis added.

34. Hirst and Dunkerton, at 131 note 11.

35. Hirst (2011) at 40.

36. Gould (1962), op cit at 94-95. Many of these alternative attributions must now of course be read subject to the qualification that they were made before the discovery of the various pieces of supporting documentation that have been brought to light in the last few decades.

37. Robinson was Superintendent of the Art Collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum and later surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures.

38. Daley, M, “No anatomical logic in Michelangelo’s defence”, The Independent 29 Sept 1994; “Michelangelo’s The Entombment: a cuckoo in the National’s nest”, Art Review, Oct 1994.

39. Vasari, op cit at 277.

40. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 70 and 123 Alternatively, it has been suggested that as the blue was so expensive, Michelangelo may have been waiting for it to be supplied by his patron (Finlay, op cit at 266, citing Langmuir, E, National Gallery Companion Guide, National Gallery Publications, 1994).

41. Dunkerton in Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 116. Overall, Dunkerton considers that the order in which the painting has been left unfinished often seems “inexplicably random” (at 113).

42. Hirst and Dunkerton, op cit at 71.

43. Spike, op cit, at 133.

44. Rab Hatfield, The Wealth of Michelangelo, Editioni di Storia e Letteratura, Rome 2002, cited in Spike, op cit at 132.

© Copyright Philip McCouat 2012, 2013, 2014, 2020

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "Michelangelo's disputed Entombment", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Return to HOME