A very rich book for the very rich

The ‘January’ miniature from The Limbourg brothers ‘Très Riches Heures of the Duke de Berry’

By Philip McCouat For comments on this article see here

introduction

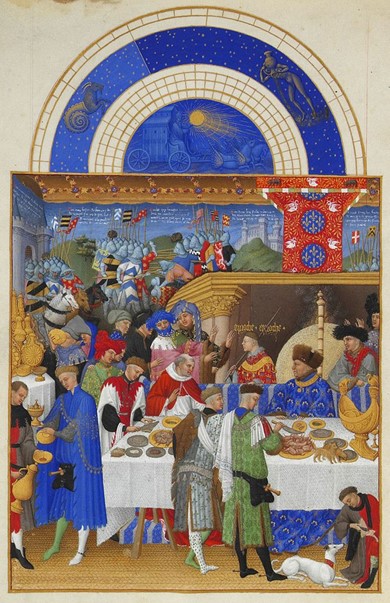

The Book of Hours known as the Très Riches Heures of the Duke du Berry is probably the most famous illuminated manuscript in the world. It is also one of the most valuable – it’s essentially priceless -- and certainly one of the most beautiful. It is highlighted by a series of miniature illustrations based on the months of the year, from January through to December, and it is the first of these (Fig 1) which we shall be examining in this article. But to do that, we must first understand what a Book of Hours was and why it came to be so important.

Evolution of the Book of Hours

Books of Hours emerged some time during the 12th century. They were originally just small prayerbooks intended for personal use in everyday devotions, containing the words of prayers which were appropriate to be said at specific hours of the day [1]. Belonging to an age before printing, they were essentially one-offs, and were primarily made for wealthy citizens.

As time went by, coloured miniature illustrations began to be included [2]. As the contents became progressively more elaborate and sophisticated, so did the covers, even to the extent of including jewels. By the 15th century, prestigious artists were being commissioned to produce works that outshone the prayers themselves, and this transformed the once-simple prayerbooks into collector items. The Très Riches Heures represents a pinnacle in this development.

What did the Books contain? In addition to the texts of prayers, they typically included a register of Church feast days, and miniature cycles of Christian events such as the Annunciation, Nativity and Life of Christ, together with Old Testament scenes. Importantly for our purposes, they also included a Calendar Year, typically with illustrations of the activities appropriate to that time of year, such as pruning in March or ploughing in October. In the case of January, when the cold weather curtailed outside activity, this was traditionally the time of leisure and festivity, so the relevant illustration would typically feature a generic aristocrat presiding over a banquet. This tradition was followed in the January miniature appearing in the Très Riches Heures, with the added feature that the aristocrat was a famous, named identity – Jean, Duke de Berry, who commissioned the book.

The Très Riches Heures consists of 206 sheets of vellum (fine parchment made from the skin of a calf) measuring just 29 by 21 cms, about the size of a sheet of standard A4 printing paper. The illustrations are in what is called the “International Gothic” style which had spread across Europe, and which represented a transitional style between Gothic and the Renaissance. The complexity and precision of the illustrations is amazing, considering their small size, and it is in fact their beauty and sumptuousness that gave rise to the title of the Book -- in the Duke of Berry’s records, kept by Robinet d’Estampes, Keeper of the Jewels, it is described as “a very rich book of hours”.

As time went by, coloured miniature illustrations began to be included [2]. As the contents became progressively more elaborate and sophisticated, so did the covers, even to the extent of including jewels. By the 15th century, prestigious artists were being commissioned to produce works that outshone the prayers themselves, and this transformed the once-simple prayerbooks into collector items. The Très Riches Heures represents a pinnacle in this development.

What did the Books contain? In addition to the texts of prayers, they typically included a register of Church feast days, and miniature cycles of Christian events such as the Annunciation, Nativity and Life of Christ, together with Old Testament scenes. Importantly for our purposes, they also included a Calendar Year, typically with illustrations of the activities appropriate to that time of year, such as pruning in March or ploughing in October. In the case of January, when the cold weather curtailed outside activity, this was traditionally the time of leisure and festivity, so the relevant illustration would typically feature a generic aristocrat presiding over a banquet. This tradition was followed in the January miniature appearing in the Très Riches Heures, with the added feature that the aristocrat was a famous, named identity – Jean, Duke de Berry, who commissioned the book.

The Très Riches Heures consists of 206 sheets of vellum (fine parchment made from the skin of a calf) measuring just 29 by 21 cms, about the size of a sheet of standard A4 printing paper. The illustrations are in what is called the “International Gothic” style which had spread across Europe, and which represented a transitional style between Gothic and the Renaissance. The complexity and precision of the illustrations is amazing, considering their small size, and it is in fact their beauty and sumptuousness that gave rise to the title of the Book -- in the Duke of Berry’s records, kept by Robinet d’Estampes, Keeper of the Jewels, it is described as “a very rich book of hours”.

So, what is happening in the painting?

In the miniature for January, the occasion is a New Year’s Day gathering and feast, possibly I January 1413, at the Paris city palace of the Duke du Berry [3], this being the traditional day for the giving of gifts (“étrenne”). This was a custom that dated back to Roman times and developed into an important feature of 15th century court culture, with the exchange of gifts being a sign of the mutual obligation between the lord and his subjects, and also a sign of goodwill in diplomatic relationships [4].

In the painting, we can see the Duke de Berry, in full profile view at the far right, sitting at the long, white-clothed table, watching new guests arrive (Fig 2). Reflecting his rank and importance, he is differentiated from the other people in various ways – he is highlighted by the golden, halo-like fire screen, and even appears to be slightly larger than the others. He wears a fur cap and a distinctive, deep blue brocade robe embroidered with gold thread. Behind him, there is a large fireplace, partly hidden by the fire screen made of woven willow twigs. Wisps of smoke reveal that the fire is burning.

Above the fireplace (see Fig 1) is a red canopy (“baldachin”), signifying the presence of a person of rank. It is decorated with the royal fleurs de lis inside the blue circles, and by the Duke’s own two heraldic animals, white swans and – at the top -- two bears. As we can see here, a swan and a bear also appear at either end of the gold boat (“nef”), on the table at far right [5].

In the painting, we can see the Duke de Berry, in full profile view at the far right, sitting at the long, white-clothed table, watching new guests arrive (Fig 2). Reflecting his rank and importance, he is differentiated from the other people in various ways – he is highlighted by the golden, halo-like fire screen, and even appears to be slightly larger than the others. He wears a fur cap and a distinctive, deep blue brocade robe embroidered with gold thread. Behind him, there is a large fireplace, partly hidden by the fire screen made of woven willow twigs. Wisps of smoke reveal that the fire is burning.

Above the fireplace (see Fig 1) is a red canopy (“baldachin”), signifying the presence of a person of rank. It is decorated with the royal fleurs de lis inside the blue circles, and by the Duke’s own two heraldic animals, white swans and – at the top -- two bears. As we can see here, a swan and a bear also appear at either end of the gold boat (“nef”), on the table at far right [5].

Fig 2: Detail of Duke de Berry at table, Limbourg Brothers, miniature illustration for the month of January, from Très Riches Heures of the Duke de Berry, 1412-16

Fig 2: Detail of Duke de Berry at table, Limbourg Brothers, miniature illustration for the month of January, from Très Riches Heures of the Duke de Berry, 1412-16

You may initially be confused to see that two armies appear to be fighting in the background of the painting, but this is just a large tapestry, intended to seal the room from draughts and provide rich decoration (Fig 3). It depicts a scene from the Trojan War, but although this took place in about 1200BC, the combatants are clothed and armed more like contemporary warriors from the 15th century.

In the midground of the painting, at far left, the Duke’s gold plate, possibly including some of the day’s gifts, is stacked high on the sideboard (Fig 4). These gold pitchers, cups and bowls are a conspicuous, portable signs of the Duke’s wealth and power [6].

New arrivals are filing in, evidently chilled from the outside cold, holding their hands up to get the warmth of the fire. A court official, probably a chamberlain, welcomes them, inviting them to approach. His words, “approche, approche”, appear in gilded writing above him. Near them, at the table, the man in clerical garb is probably Martin Gouge, the Duke’s treasurer and Bishop of Chartres.

In the foreground, at left, a courtier is fetching a drink, and possibly a finger bowl, for the Duke. Both the goblet and the bowl have lids, a privilege reserved for rulers [7]. Further along the table (see Fig 2), a carver with a large knife is about to cut up the fowl on the large platter, with the choicest parts being, of course, reserved for the Duke. In accordance with custom, he will eat them using the first three fingers of his right hand, (hence the need for the finger bowl) [8]. This would just be one of the many courses that would be served – according to the Duke’s expense ledgers, every Sunday and feast day, the menu would include three oxen, thirty sheep, and over 300 partridges and hares. After all, the ducal household was numbered in the hundreds!

New arrivals are filing in, evidently chilled from the outside cold, holding their hands up to get the warmth of the fire. A court official, probably a chamberlain, welcomes them, inviting them to approach. His words, “approche, approche”, appear in gilded writing above him. Near them, at the table, the man in clerical garb is probably Martin Gouge, the Duke’s treasurer and Bishop of Chartres.

In the foreground, at left, a courtier is fetching a drink, and possibly a finger bowl, for the Duke. Both the goblet and the bowl have lids, a privilege reserved for rulers [7]. Further along the table (see Fig 2), a carver with a large knife is about to cut up the fowl on the large platter, with the choicest parts being, of course, reserved for the Duke. In accordance with custom, he will eat them using the first three fingers of his right hand, (hence the need for the finger bowl) [8]. This would just be one of the many courses that would be served – according to the Duke’s expense ledgers, every Sunday and feast day, the menu would include three oxen, thirty sheep, and over 300 partridges and hares. After all, the ducal household was numbered in the hundreds!

In the foreground of the painting, at right, resting on the straw matting, is the Duke’s greyhound, being fed by one of its own attendants (Fig 1). This was one of the Duke’s many hundreds of dogs. His favourites included the tiny ones, identified as Pomeranian spitzes, which you can see are actually standing on the table, scouting for morsels [9]. At various times, the Duke also collected exotic animals, such as a leopard, camel, monkey or ostrich.

The richness of costume, decoration and precious objects in the painting is enhanced by the plentiful use of vibrant expensive colour pigments from exotic sources. Gold, ultramarine blue made from the precious lapis lazuli, green from Hungarian malachite, vermilion red made from quicksilver and sulphur, are all prominent [10].

Above this scene of intense social activity is a semi-circular depiction of the heavens (Fig 5), reflecting the relevance of the time of year and position of stars to agricultural and social activities. Inside the inner semicircle, Apollo drives the radiant sun across the heavens in his chariot. In the outer semi-circle are the Zodiac signs for January -- the half goat/half fish Capricorn, and Aquarius the Water Carrier.

The richness of costume, decoration and precious objects in the painting is enhanced by the plentiful use of vibrant expensive colour pigments from exotic sources. Gold, ultramarine blue made from the precious lapis lazuli, green from Hungarian malachite, vermilion red made from quicksilver and sulphur, are all prominent [10].

Above this scene of intense social activity is a semi-circular depiction of the heavens (Fig 5), reflecting the relevance of the time of year and position of stars to agricultural and social activities. Inside the inner semicircle, Apollo drives the radiant sun across the heavens in his chariot. In the outer semi-circle are the Zodiac signs for January -- the half goat/half fish Capricorn, and Aquarius the Water Carrier.

“The most covetous man in the world”

The Duke was intimately connected to the sources of power in France. He was the third son of King John II, the brother of King Charles V and the uncle of the then-current King Charles VI. At various stages he was Lieutenant General for numerous provinces and acted as co-regent of France during Charles VI’s minority. He became one of most dominant figures in the country, attracting the appellation “Jean the Magnificent”.

He was also one of the greatest patrons of art, indulging in what amounted to a “frenzy of accumulation” [11]. He had an addiction to collecting and commissioning valuable objects such as illuminated books, paintings, sculptures and jewellery, patronising artists and splurging money on lavish entertainments which he believed fitting to a person of his rank. As well, he was obsessed with building extravagant palaces, in Paris and in the provinces of Berry, Auvergne and Poitou, which he controlled [12]. By the time of Très Riches Heures, he had accumulated no fewer than 17 palaces and other major residences. He and his sizeable retinue would regularly travel between them, carrying with them portable furnishings, including tapestries, such as the one we have already seen in the miniature [13].

But this profligacy, coupled with his willingness to assume crippling debts, meant that his financial difficulties became chronic. His desperate efforts to raise money by increasing taxes caused considerable unrest amongst the populace. According to the court historian Jean Froissart, “the Duke was the most covetous man in the world and did not care where he took his money” [14]. Even at the time of his later death, he would remain deeply in debt.

He was also one of the greatest patrons of art, indulging in what amounted to a “frenzy of accumulation” [11]. He had an addiction to collecting and commissioning valuable objects such as illuminated books, paintings, sculptures and jewellery, patronising artists and splurging money on lavish entertainments which he believed fitting to a person of his rank. As well, he was obsessed with building extravagant palaces, in Paris and in the provinces of Berry, Auvergne and Poitou, which he controlled [12]. By the time of Très Riches Heures, he had accumulated no fewer than 17 palaces and other major residences. He and his sizeable retinue would regularly travel between them, carrying with them portable furnishings, including tapestries, such as the one we have already seen in the miniature [13].

But this profligacy, coupled with his willingness to assume crippling debts, meant that his financial difficulties became chronic. His desperate efforts to raise money by increasing taxes caused considerable unrest amongst the populace. According to the court historian Jean Froissart, “the Duke was the most covetous man in the world and did not care where he took his money” [14]. Even at the time of his later death, he would remain deeply in debt.

The talented Limbourg brothers

The miniatures in the Très Riches Heures were painted by the Limbourg brothers, Paul, Jean and Herman, from Nijmegen, in the Netherlands [15]. The brothers came from an artistic family: their father was a sculptor and an uncle was an established painter who worked for the Duke de Berry’s brother, Philip the Bold [16]. At least two of the Limbourg brothers were apprenticed as goldsmiths.

It was Philip who gave the brothers their first major commission, to illustrate a bible. After Philip died, the Duke commissioned them to illustrate the Book of Hours which would come to be known as the Belles Heures du Duc de Berry. After they finished this in 1409, the Duke commissioned them to do what became the Très Riches Heures. It would be the Duke’s fifteenth luxury Book of Hours, and it would be a masterpiece.

The brothers worked on the project from 1412 to 1416. They no doubt shared the work between themselves, though it may be that Paul, the more senior, took the lead role. It is likely that other artists did the border decorations. In addition to the agreed payment, Paul was made a chamberlain to the Duke, quite a prestigious honour. The Duke also gifted Paul a house and, it appears, even procured a young girl named Guillotte to marry him [17]. It is speculated that a portrait of Paul Limbourg, wearing a grey floppy headpiece appears in the crowd (Fig 4) and the brothers (or possibly one brother and Guillotte) appear next to him. There have been attempts to identify other persons [18], but this issue is substantially speculative [19]. Attempts to identify exactly which each Limbourg brother contributed have also been made [20], but this issue, too, is largely a matter of speculation.

In the light of the book’s current fame, it may seem strange to note that after 1530, both it, and the Limbourgs, became largely forgotten for hundreds of years. However, this is perhaps not so surprising, bearing in mind that these works were one-offs, were largely inaccessible and had such a limited audience. They were ultimately “rediscovered” – in a “boarding school for young ladies” -- by bibliophile Henri d’Orleans when he acquired the book in 1856. And, of course, this very fortuitous discovery has only added to the book’s “cultic status” [21].

It was Philip who gave the brothers their first major commission, to illustrate a bible. After Philip died, the Duke commissioned them to illustrate the Book of Hours which would come to be known as the Belles Heures du Duc de Berry. After they finished this in 1409, the Duke commissioned them to do what became the Très Riches Heures. It would be the Duke’s fifteenth luxury Book of Hours, and it would be a masterpiece.

The brothers worked on the project from 1412 to 1416. They no doubt shared the work between themselves, though it may be that Paul, the more senior, took the lead role. It is likely that other artists did the border decorations. In addition to the agreed payment, Paul was made a chamberlain to the Duke, quite a prestigious honour. The Duke also gifted Paul a house and, it appears, even procured a young girl named Guillotte to marry him [17]. It is speculated that a portrait of Paul Limbourg, wearing a grey floppy headpiece appears in the crowd (Fig 4) and the brothers (or possibly one brother and Guillotte) appear next to him. There have been attempts to identify other persons [18], but this issue is substantially speculative [19]. Attempts to identify exactly which each Limbourg brother contributed have also been made [20], but this issue, too, is largely a matter of speculation.

In the light of the book’s current fame, it may seem strange to note that after 1530, both it, and the Limbourgs, became largely forgotten for hundreds of years. However, this is perhaps not so surprising, bearing in mind that these works were one-offs, were largely inaccessible and had such a limited audience. They were ultimately “rediscovered” – in a “boarding school for young ladies” -- by bibliophile Henri d’Orleans when he acquired the book in 1856. And, of course, this very fortuitous discovery has only added to the book’s “cultic status” [21].

A disastrous outcome

In many ways, the New Years’ celebration depicted in the January miniature represented a turning point in the fortunes not only of the Duke, but also of the Limbourgs and even France itself. Shortly after, the Duke fell seriously ill, contributing in part to a new eruption of civil war and breakdown in law and order in a country already been weakened by outbreaks of the Plague and decades of sporadic warfare. In 1415 the English took advantage of the new bout of unrest and invaded, with Henry V’s army achieving decisive victory at the Battle of Agincourt. The next year, the Duke died, reputedly so short of money that there was not enough to pay for his funeral.

In the same year, the three Limbourg brothers also died, presumably of the Plague. The book was still unfinished at their death, and was finally completed in later decades, reputedly by illuminators Barthélemy d’Eyck and Jean Colombe. The exact attributions of these later contributors are a matter of much academic and scholarly debate [22].

In the same year, the three Limbourg brothers also died, presumably of the Plague. The book was still unfinished at their death, and was finally completed in later decades, reputedly by illuminators Barthélemy d’Eyck and Jean Colombe. The exact attributions of these later contributors are a matter of much academic and scholarly debate [22].

Conclusion

Luxury Books of Hours such as the Très Riches Heures eventually fell out of fashion in the early 16th century, a decline accelerated by the invention of printing. Today, they are generally museum pieces, or held in exclusive private collections. Ironically, however, in this age of reproduction, they are now more accessible than they ever have been, through websites and popular art books [23]. Apart from their undoubted aesthetic appeal, they remain potent reminders of the age and society in which they were created■

© Philip McCouat, 2021

First published May 2021

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “A very rich book for the very rich: the ‘January’ miniature from The Limbourg brothers ‘Très Riches Heures of the Duke de Berry’”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

Your comments on this article are welcomed

RETURN TO HOME

© Philip McCouat, 2021

First published May 2021

This article may be cited as Philip McCouat, “A very rich book for the very rich: the ‘January’ miniature from The Limbourg brothers ‘Très Riches Heures of the Duke de Berry’”, Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

Your comments on this article are welcomed

RETURN TO HOME

End notes

[1] Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen, “Palaces crumble but books remain”, in What Great Paintings Say, Vol 2, Taschen, Cologne, 2003 at 22ff

[2] The word “miniature” is derived from the Latin “minium”, meaning orange/red, a colour used in decorating (“illuminating”) the initial letter of each prayer: Hagen, op cit at 22

[3] Hagen, op cit at 22

[4] This traditional form of gift-giving, and reciprocity in general, is fully discussed in Brigitte Buettner, "Past Presents: New Year's Gifts at the Valois Courts, ca. 1400," Art Bulletin, 83, 2001, pp. 598-625

[5] Buettner, op cit at 612

[6] Hagen, op cit at 25

[7] Hagen, op cit at 26

[8] Hagen, op cit at 26

[9] Hagen, op cit at 26

[10] Lillian Schacherl, Très Riches Heures: Behind the Gothic Masterpiece, transl Fiona Elliott, Prestel, 1907

[11] Michael Camille (1), “‘For our Devotion and Pleasure’: The sexual objects of Jean Duke du Berry”, Art History, Vol 24 No 2, April 2001, 169-194

[12] Hagen, op cit at 24

[13] Wendy A Stein, “Patronage of Jean de Berry (1340—1416)”, Essay, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, May 2009, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/berr/hd_berr.htm

[14] Camille (1), op cit at 172

[15] Christine M Bolli, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “The Art of Illumination; Herman, Paul and Jean de Limbourg” http://blog.metmuseum.org/artofillumination/the-artists-herman-paul-and-jean-de-limbourg/

[16] Philip was the Duke of Burgundy

[17] Hagen, op cit at 27

[18] Notably by Saint-Jean Bourdin, among others

[19] Michael Camille (2), "The Très Riches Heures: An Illuminated Manuscript in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." Critical Inquiry, vol. 17 (Autumn), pp. 72–107 at 99

[20] Millard Meiss, The Limbourgs and Their Contemporaries, 1974

[21] Camille (2), op cit at 73 ff

[22] Camille (2), op cit at 95

[23] Of course, sometimes this comes at a price -- in 1981 the exclusive right to produce the first facsimile edition of the Très Riches Heures was granted to Facsimile Editions Lucerne. Each facsimile book cost $12,000: Camille (2), op cit at 72.

© Philip McCouat, 2021

RETURN TO HOME

[2] The word “miniature” is derived from the Latin “minium”, meaning orange/red, a colour used in decorating (“illuminating”) the initial letter of each prayer: Hagen, op cit at 22

[3] Hagen, op cit at 22

[4] This traditional form of gift-giving, and reciprocity in general, is fully discussed in Brigitte Buettner, "Past Presents: New Year's Gifts at the Valois Courts, ca. 1400," Art Bulletin, 83, 2001, pp. 598-625

[5] Buettner, op cit at 612

[6] Hagen, op cit at 25

[7] Hagen, op cit at 26

[8] Hagen, op cit at 26

[9] Hagen, op cit at 26

[10] Lillian Schacherl, Très Riches Heures: Behind the Gothic Masterpiece, transl Fiona Elliott, Prestel, 1907

[11] Michael Camille (1), “‘For our Devotion and Pleasure’: The sexual objects of Jean Duke du Berry”, Art History, Vol 24 No 2, April 2001, 169-194

[12] Hagen, op cit at 24

[13] Wendy A Stein, “Patronage of Jean de Berry (1340—1416)”, Essay, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, May 2009, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/berr/hd_berr.htm

[14] Camille (1), op cit at 172

[15] Christine M Bolli, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “The Art of Illumination; Herman, Paul and Jean de Limbourg” http://blog.metmuseum.org/artofillumination/the-artists-herman-paul-and-jean-de-limbourg/

[16] Philip was the Duke of Burgundy

[17] Hagen, op cit at 27

[18] Notably by Saint-Jean Bourdin, among others

[19] Michael Camille (2), "The Très Riches Heures: An Illuminated Manuscript in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." Critical Inquiry, vol. 17 (Autumn), pp. 72–107 at 99

[20] Millard Meiss, The Limbourgs and Their Contemporaries, 1974

[21] Camille (2), op cit at 73 ff

[22] Camille (2), op cit at 95

[23] Of course, sometimes this comes at a price -- in 1981 the exclusive right to produce the first facsimile edition of the Très Riches Heures was granted to Facsimile Editions Lucerne. Each facsimile book cost $12,000: Camille (2), op cit at 72.

© Philip McCouat, 2021

RETURN TO HOME