The art of giraffe diplomacy

How an African giraffe walked across France and became a pawn in an international power struggle

By Philip McCouat

You can hear Philip speaking about this article on Derek Mooney’s documentary broadcast on 26/12/22 on Irish RTÉ Radio 1. It’s available at https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22190081/

You can hear Philip speaking about this article on Derek Mooney’s documentary broadcast on 26/12/22 on Irish RTÉ Radio 1. It’s available at https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22190081/

Introduction

In the cool, dark archives of the Museum of Natural History in Paris, you may come across the “Vellum Collection”, a hundred red leather-bound volumes containing 7,000 beautifully detailed drawings of plants, animals and birds [1]. These rarely-visited treasures are relics of the pre-photographic era, in which our only source of images of natural life came from the hands of artists [2].

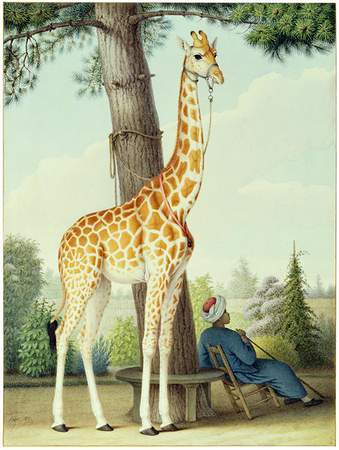

Many of the animals depicted in the drawings once lived in the Museum’s “Jardin des Plantes”. The Jardin was France’s most important botanical garden, and also contained the world’s oldest municipal zoo. And one of the Jardin’s most celebrated inhabitants was a giraffe – the very first giraffe ever seen in France – which, in 1826, created a national sensation when it arrived as a diplomatic gift from Egypt and walked right across France to meet the King.

Many of the animals depicted in the drawings once lived in the Museum’s “Jardin des Plantes”. The Jardin was France’s most important botanical garden, and also contained the world’s oldest municipal zoo. And one of the Jardin’s most celebrated inhabitants was a giraffe – the very first giraffe ever seen in France – which, in 1826, created a national sensation when it arrived as a diplomatic gift from Egypt and walked right across France to meet the King.

This article explores the odd conjunction of events which led to the giraffe’s extraordinary arrival, to the way in which it was portrayed and to its ecstatic reception by the French public – and how that fascination has survived to this day.

A tangled political situation

What prompted Egypt to go to the considerable expense and effort of procuring and sending a live giraffe to the French king? The answer lies in the tangled political situation of the Ottoman Empire at the time.

The Empire, from its base in Constantinople [3], had once been vast. At its greatest extent, in the late 16th century, it had spread from Budapest in the north to the Sudan in the south, Morocco in the west and the Caspian Sea in the east. But, by the 1820s, the Empire was in serious decline.

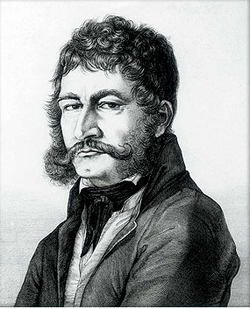

At this time, although Egypt was a significant component of the Empire, the Ottoman Sultan took little interest in that country as long as his annual taxes were paid on time [4]. With the local Egyptian government also being weak, there was effectively a power vacuum. Into this stepped Mohammed Ali, an ambitious officer in the Turkish army in Egypt (Fig 2). Originally an Albanian mercenary, Ali had risen rapidly through the ranks and eventually was able to assume total control into his own hands. He became to all intents and purposes the self-appointed independent ruler of the Nile Valley [5], with personal interests that did not necessarily jibe with those of his nominal masters in Constantinople.

The Empire, from its base in Constantinople [3], had once been vast. At its greatest extent, in the late 16th century, it had spread from Budapest in the north to the Sudan in the south, Morocco in the west and the Caspian Sea in the east. But, by the 1820s, the Empire was in serious decline.

At this time, although Egypt was a significant component of the Empire, the Ottoman Sultan took little interest in that country as long as his annual taxes were paid on time [4]. With the local Egyptian government also being weak, there was effectively a power vacuum. Into this stepped Mohammed Ali, an ambitious officer in the Turkish army in Egypt (Fig 2). Originally an Albanian mercenary, Ali had risen rapidly through the ranks and eventually was able to assume total control into his own hands. He became to all intents and purposes the self-appointed independent ruler of the Nile Valley [5], with personal interests that did not necessarily jibe with those of his nominal masters in Constantinople.

Ali was capable but ruthless, engaging in massive slave trading from other parts of Africa to provide the labour needed for his redevelopment and infrastructure plans in Egypt. His determination to drag Egypt into the modern era led him to welcome foreign industrialists and developers, merchants, diplomats and tourists. The monuments of ancient Egypt were of little interest to him – he called them “ancient debris” [6] – suitable only for fostering public relations with Europe. Under Ali’s rule, Egypt was soon being stripped of its archaeological treasures by a steady stream of collectors, dealers and profiteers [7].

By the 1820s, with the decline of the Empire, a number of its outposts were in a state of revolt. Notable among these was Greece, which had been conquered by the Ottoman Turks back in the 15th century. Spurred by the recent revolutions in America and France, the Greek rebels’ early successes in their own War of Independence spurred the Sultan to call for help from Ali and his huge Egyptian army of Sudanese slaves. Ali was offered the reward of Crete if the revolt could be crushed.

Ali’s consequent intervention in Greece, embellished with lurid reports of atrocities, prompted French and English calls to intervene on the side of the embattled Greeks. The Russians too threatened to come to the aid of the (Christian) insurgents against their (Muslim) foes. Ali now found himself in a potentially difficult situation, a victim of his own success, with the possibility of his Greek venture alienating the valued European support he had worked so hard to nurture.

By the 1820s, with the decline of the Empire, a number of its outposts were in a state of revolt. Notable among these was Greece, which had been conquered by the Ottoman Turks back in the 15th century. Spurred by the recent revolutions in America and France, the Greek rebels’ early successes in their own War of Independence spurred the Sultan to call for help from Ali and his huge Egyptian army of Sudanese slaves. Ali was offered the reward of Crete if the revolt could be crushed.

Ali’s consequent intervention in Greece, embellished with lurid reports of atrocities, prompted French and English calls to intervene on the side of the embattled Greeks. The Russians too threatened to come to the aid of the (Christian) insurgents against their (Muslim) foes. Ali now found himself in a potentially difficult situation, a victim of his own success, with the possibility of his Greek venture alienating the valued European support he had worked so hard to nurture.

An exotic diplomatic gift

A possible solution to Ali’s problem was suggested by the charismatic Bernadino Drovetti, possibly the most influential European in Egypt (Fig 3) [8]. Drovetti, as France’s consul-general in Egypt, was an entrepreneurial middle-man who acted as an influential private adviser to Ali, and himself made a fortune from exporting and selling huge amounts of Egyptian antiquities to European markets.

Drovetti had for some time been ingratiating himself with the newly-crowned French King, Charles X, by sending African animals such as parrots, hyenas and wild cats to Paris to stock the king’s menagerie. He now suggested that Ali could achieve the French king’s royal favour by a diplomatic gift of an animal so quintessentially strange, exotic and striking that it could not fail to impress the French, and – hopefully – soothe their fears about Ali’s warlike and expansionist tendencies. That animal, as you no doubt would have guessed by now, was the giraffe.

Drovetti had for some time been ingratiating himself with the newly-crowned French King, Charles X, by sending African animals such as parrots, hyenas and wild cats to Paris to stock the king’s menagerie. He now suggested that Ali could achieve the French king’s royal favour by a diplomatic gift of an animal so quintessentially strange, exotic and striking that it could not fail to impress the French, and – hopefully – soothe their fears about Ali’s warlike and expansionist tendencies. That animal, as you no doubt would have guessed by now, was the giraffe.

Giraffes in diplomacy and art

Actually, Drovetti’s idea was not as novel as might first appear. Giraffes have been used as diplomatic “gifts” for thousands of years, the ancient forerunners of the “giant panda” diplomacy that China conducted with the United States in the 1970s [8a].

Part of their appeal has been the sheer unlikehood of such an extraordinarily-proportioned animal even existing. It has been reported that, even today, many people who see giraffes for the first time on a prairie in Africa see only one animal where there are actually several. “Giraffes are so unusual they seem to overwhelm the senses. The brain does not know what to do with its input” [9].

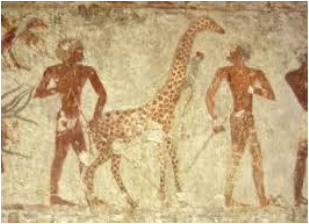

As natives of Africa, giraffes were known in ancient Egypt, and were commonly depicted in their wall paintings (Fig 4). Giraffe tails were actually presented as tribute to Tutankhamun in the 14th century BC [10]. They were also represented in the rock art of the African Bushmen and the Hottentots [11].

Part of their appeal has been the sheer unlikehood of such an extraordinarily-proportioned animal even existing. It has been reported that, even today, many people who see giraffes for the first time on a prairie in Africa see only one animal where there are actually several. “Giraffes are so unusual they seem to overwhelm the senses. The brain does not know what to do with its input” [9].

As natives of Africa, giraffes were known in ancient Egypt, and were commonly depicted in their wall paintings (Fig 4). Giraffe tails were actually presented as tribute to Tutankhamun in the 14th century BC [10]. They were also represented in the rock art of the African Bushmen and the Hottentots [11].

n China, a giraffe first appeared in the early 15th century, captured when the Chinese fleet had visited East Africa. It was presented to the Chinese Emperor Zhu Di, who immediately proclaimed it as a sign of heavenly blessing for his rule. His claim was based on a totally fictitious linkage of the giraffe to the legendary Chinese animal the quilin, which was said to have the body of a musk deer, the tail of an ox, the forehead of a wolf, the hoofs of a horse and a fleshy horn like a unicorn [12]. This giraffe was the first of many such tributes in later decades -- contemporary Chinese paintings of giraffes were clearly done from study of these live animals sent as gifts to imperial court [13].

In Europe, the first giraffe had been one brought from Cleopatra’s Egypt by Julius Caesar in 46BC [14]. Caesar’s intentions, however, were neither diplomatic nor philanthropic. The giraffe marched in his triumphal procession and, reportedly, hundreds were later imported for the Circus Games, to be mauled by lions as a public spectacle for the pleasure of the Roman audiences [15]. The Romans called giraffes “camelopards”, based on the idea that they were composite creatures with the characteristics of both a camel and a leopard. Camelopardalis is still used today as its species name.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, giraffes were essentially forgotten in most parts of Europe for almost a thousand years, re-appearing in a Sicilian menagerie during the 13th century and in English literature in The Travels of Sir John Mandeville (c 1356).

Most spectacular, however, was the appearance of a tame 16-foot tall giraffe which was imported from Cairo to the Italian city of Florence in 1487. The giraffe had been a crucial bargaining chip in tough negotiations between the Egyptian Sultan and the Florentine leader Lorenzo de’ Medici, who had a burning desire to emulate Caesar’s giraffe exploits in order to add to his own power, prestige and mystique [16].

In Europe, the first giraffe had been one brought from Cleopatra’s Egypt by Julius Caesar in 46BC [14]. Caesar’s intentions, however, were neither diplomatic nor philanthropic. The giraffe marched in his triumphal procession and, reportedly, hundreds were later imported for the Circus Games, to be mauled by lions as a public spectacle for the pleasure of the Roman audiences [15]. The Romans called giraffes “camelopards”, based on the idea that they were composite creatures with the characteristics of both a camel and a leopard. Camelopardalis is still used today as its species name.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, giraffes were essentially forgotten in most parts of Europe for almost a thousand years, re-appearing in a Sicilian menagerie during the 13th century and in English literature in The Travels of Sir John Mandeville (c 1356).

Most spectacular, however, was the appearance of a tame 16-foot tall giraffe which was imported from Cairo to the Italian city of Florence in 1487. The giraffe had been a crucial bargaining chip in tough negotiations between the Egyptian Sultan and the Florentine leader Lorenzo de’ Medici, who had a burning desire to emulate Caesar’s giraffe exploits in order to add to his own power, prestige and mystique [16].

The Medici giraffe, though it only survived in Florence for a short time, proved to be a sensation, being recorded by writers such as Angelo Poliziano [17], and inspiring numerous paintings by artists such as Vasari and da Faenza (Fig 5), and Andrea del Sarto (for example, in Journey of the Magi, 1511 and The Triumph of Caesar 1521). So desirable was it that it aroused a surprising passion in Anne de Beaujeu, daughter of Louis XI, who believed that Lorenzo had promised to present her with the giraffe, which she considered “the beast of the world that I have the greatest desire to see” [18]. To this day, one of the seventeen neighbourhoods of nearby Siena is named after the giraffe (the Contrada della Giraffa), and she is commemorated on its riding team and their racing silks [19].

First, catch your giraffe

So Drovetti’s giraffe idea had a long historical lineage, and Ali went for it. Characteristically, he acted swiftly. Even so, it took some months for his edict to reach Khartoum and for Arab hunters to reach the savannah highlands of what was then called Ethiopia (now southeastern Sudan). There they located a mother and young two-month old female calf. The mother was killed, and the newly-orphaned baby giraffe, with its hoofs bound, was strapped aboard a camel [19a] actually two calves were captured but the second, intended to curry favour with the British, was frailer. Partly crippled by her period of being bound, she was unable to support her own weight, did not thrive and died shortly after reaching England.] Initially the giraffe was hand-fed with camels’ milk and, later, cows provided the gallons of milk required each day for her to thrive [20].

The giraffe was shipped down the Blue Nile aboard a felucca to the recently-established garrison at Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, where she stayed to mature and strengthen [21]. Conveniently, she was still relatively small and easy to handle [22].

The giraffe was shipped down the Blue Nile aboard a felucca to the recently-established garrison at Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, where she stayed to mature and strengthen [21]. Conveniently, she was still relatively small and easy to handle [22].

The journey to paris begins

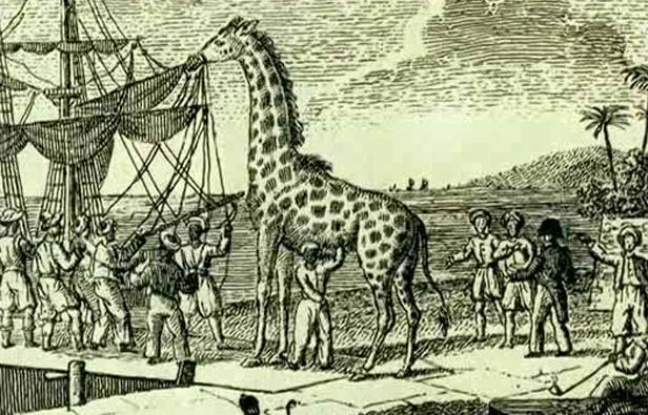

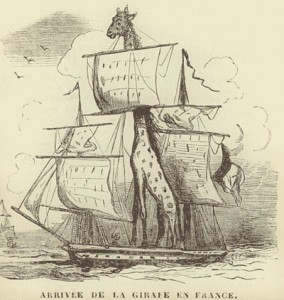

From Khartoum, the giraffe embarked upon an epic two-year journey to Paris. First, it travelled aboard a specially constructed barge, following the slave trail northwards along the entire length of the Nile, nearly 2,000 miles to Alexandria on the Mediterranean (Fig 6). At this stage, she was being accompanied by Drovetti’s Arab groom Hassan, and his Sudanese servant Atir [22a].

Then followed another four weeks’ sea voyage to the French seaport of Marseille. During her time at sea, the giraffe travelled standing in the hold with her long neck and head protruding through a hole cut in the deck, shaded by a canvas tent. When she finally stepped ashore at Marseille in October 1826, she became the first giraffe to be seen in Europe for over 300 years.

After a period of quarantine, she overwintered in Marseille, going on regular walks which rapidly became public events. Sweet-natured, friendly and frisky [23], she sometimes bounded like a young horse or even broke into a gallop – giraffes can run at up to 60 kph -- dragging along the Arabs attempting to restrain her [24]. From time to time she was exhibited for the inspection of small groups of the cream of Marseille society, where she was reported as displaying an “amiable vivacity”[25].

The marathon walk Across France

The giraffe’s adaptability, and the endurance she showed on her walks, convinced her handlers that she could walk the 900 kilometres to Paris by a series of short daily treks, rather than risk the hazards of another sea voyage around Spain.

Accordingly, on May 20 1827, a bizarre procession, complete with an escort of police, left Marseilles. It was led by one of France’s foremost scientists Ėtienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, the gout and rheumatism-afflicted head of the zoo at the Jardin des Plantes, and it included cows, an antelope, two moufflons (Corsican sheep), and a loaded provision cart. The giraffe, by now virtually fully grown at twelve feet high, was encouraged along by her handlers Hassan and Atir, and by the alluring sight of the milk-bearing cows in front of her. To protect her from rain and cold, she had her own black raincoat, embossed with the king’s fleur-de-lis coat of arms.

As shown in Brascassat’s painting of the giraffe during her journey (Fig 8), giraffes have an unusual walking style, moving both the legs on one side of the body at the same time, then doing the same on the other side. In this way, the giraffe proceeded at a steady, but stately, two miles an hour.

Accordingly, on May 20 1827, a bizarre procession, complete with an escort of police, left Marseilles. It was led by one of France’s foremost scientists Ėtienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, the gout and rheumatism-afflicted head of the zoo at the Jardin des Plantes, and it included cows, an antelope, two moufflons (Corsican sheep), and a loaded provision cart. The giraffe, by now virtually fully grown at twelve feet high, was encouraged along by her handlers Hassan and Atir, and by the alluring sight of the milk-bearing cows in front of her. To protect her from rain and cold, she had her own black raincoat, embossed with the king’s fleur-de-lis coat of arms.

As shown in Brascassat’s painting of the giraffe during her journey (Fig 8), giraffes have an unusual walking style, moving both the legs on one side of the body at the same time, then doing the same on the other side. In this way, the giraffe proceeded at a steady, but stately, two miles an hour.

During her marathon walk, the giraffe became such an unprecedented attraction that crowds virtually rioted around her. As Allin comments, “people came out of their fields and vineyards to marvel at the living mythological combination of creatures – a gentle and mysterious sort of horned camel who hump had been straightened by stretching its neck [actually a giraffe’s neck is so long because of its elongated cervical vertebrae], with legs as tall as a man and the cloven hoofs of a cow, and markings like a leopard or a maze of lightning, and that startling blue-black snake of a twenty-inch tongue” [26].

At the time, the giraffe was regarded as so unusual and distinctive that it was often simply referred to as the Giraffe, and sometimes as the king’s beautiful animal or the beautiful African. Today, you may hear her commonly referred to by the name of “Zarafa”, but it appears that this usage only follows a convention adopted in 1985 by the French Journalist Gabriel Dardaud in his Une girafe pour le roi, based on the African/Arabic word zarafa, meaning giraffe [27].

In some places, the rush of the crowds to see her reportedly resembled a cavalry charge [28]. By the time the little convoy reached Lyons, the giraffe was so famous that crowds of up to 30,000 people – almost a third of the entire population -- turned out to see her. To control the crowds the mounted police had to be aumented by military cavalry [29].

At the time, the giraffe was regarded as so unusual and distinctive that it was often simply referred to as the Giraffe, and sometimes as the king’s beautiful animal or the beautiful African. Today, you may hear her commonly referred to by the name of “Zarafa”, but it appears that this usage only follows a convention adopted in 1985 by the French Journalist Gabriel Dardaud in his Une girafe pour le roi, based on the African/Arabic word zarafa, meaning giraffe [27].

In some places, the rush of the crowds to see her reportedly resembled a cavalry charge [28]. By the time the little convoy reached Lyons, the giraffe was so famous that crowds of up to 30,000 people – almost a third of the entire population -- turned out to see her. To control the crowds the mounted police had to be aumented by military cavalry [29].

By this time, given the long wait and the growing crowds, the King had begun to wonder whether he would be the last person in France to see his own giraffe. But, eventually, after 41 days and 900 kilometres on the road, with stops at 22 towns and villages along the way, the giraffe finally reached Paris, She was ceremoniously paraded through the city and was eventually presented to the King. She was put on daily public exhibition, and in the last three weeks of July 1827, 60,000 people came to see her [30].

The giraffe was eventually installed in the zoo at the Jardin des Plantes. This was a zoo which had a rather turbulent history. Back in 1792, during the French Revolution, mobs had attacked the Tuileries palace at Versailles. They pillaged the King’s menagerie and most of the animals were “either eaten or delivered up to the flayer”. Only five animals had survived, including a lion and a rhinoceros. At the instigation of the steward of the Jardin des Plantes, these were transported to the Jardin to form the basis of a menagerie. Some 35 years later, it was this zoo, now prestigious and respectable, that became the giraffe’s new home [31].

In the next few months, over 600,000 people – locals and tourists -- visited her there, with the journal Pandore reporting with a degree of wonder that, “The giraffe occupies all the public’s attention; one talks of nothing else in the circles of the capital” [32].

The giraffe was eventually installed in the zoo at the Jardin des Plantes. This was a zoo which had a rather turbulent history. Back in 1792, during the French Revolution, mobs had attacked the Tuileries palace at Versailles. They pillaged the King’s menagerie and most of the animals were “either eaten or delivered up to the flayer”. Only five animals had survived, including a lion and a rhinoceros. At the instigation of the steward of the Jardin des Plantes, these were transported to the Jardin to form the basis of a menagerie. Some 35 years later, it was this zoo, now prestigious and respectable, that became the giraffe’s new home [31].

In the next few months, over 600,000 people – locals and tourists -- visited her there, with the journal Pandore reporting with a degree of wonder that, “The giraffe occupies all the public’s attention; one talks of nothing else in the circles of the capital” [32].

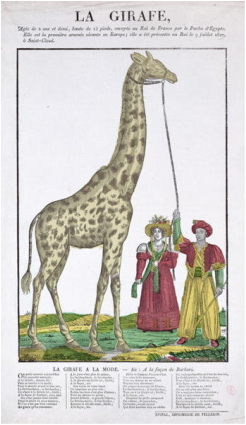

Celebrity: a cultural icon and fashion item

The giraffe was not just a sensation for its physical beauty or novelty value. As Allin notes, it became a national icon, the envy of Europe, the subject of songs and poems, cartoons , satires (Fig 10), music-hall sketches and political allegories, the namesake of public squares and even that season’s form of influenza [33]. Giraffe colours and designs were featured in jewellery, wallpaper, crockery, knickknacks, soap, confectionery (such as gingerbread giraffes, and giraffe ice creams), furniture and topiary.

In Paris, glamorous women imitated the giraffe with their hair styled high, à la Giraffe, piled so high that they supposedly had to ride on the floors of their carriages. A “new” colour “giraffe” (basically, yellowish) became fashionable in clothes and accessories and hats. Even men wore fashionably giraffique hats and ties [34].

In Paris, glamorous women imitated the giraffe with their hair styled high, à la Giraffe, piled so high that they supposedly had to ride on the floors of their carriages. A “new” colour “giraffe” (basically, yellowish) became fashionable in clothes and accessories and hats. Even men wore fashionably giraffique hats and ties [34].

As we have seen, this was not the first time giraffes had ever been seen in Europe. There had also been prior fashion crazes based on other exotic animals, such as the rhinoceros (1749) and the zebra (1786) [35]. But a number of factors combined to make the new giraffe boom quite different from its predecessors, both in nature and in scope. The first, as Majer points out, was the degree to which this boom was commercially driven and exploited. This was a relatively new phenomenon. During the 18th century a mass market had, for the first time, been created in consumer goods, clothes and knickknacks. To fuel demand, this market constantly required new fads and fashions. In 1827-8 the giraffe played its innocent part in this new trend, becoming in the process a consumer product as well as a natural wonder [36].

This process was augmented by the fact that, by the 1820s, the press --including the fashion press -- was flourishing. This was particularly conducive to the widespread dissemination of information and imagery of the giraffe. The newspapers treated her as a continuing major news story [37], and her representation appeared in thousands of lithographs, engravings and woodcuts. She also constantly appeared as a vehicle for satiric criticism of the king, particularly by those opposed to his censorship laws.

A third factor was the particular relationship that France had with Egypt. French interest in that country had been strong ever since Napoleon’s invasion in 1798, with the associated awakening of interest in Egyptian culture being spurred by the publication of the massive, magnificently illustrated ten-volume Description de l’Ėgypte [38]. Even further impetus was provided by Champollion’s decipherment of the Rosetta Stone in 1822. All this meant that by 1826 the French public was already well acquainted culturally and politically with giraffe’s country of origin [39].

Finally, the giraffe’s wide public visibility and accessibility over a prolonged period of time – from the walk across France itself, her daily walks, and from her public exhibition in the centrally located (and free) Jardin des Plantes. Far from being secreted away in the king’s private estate, she became a giraffe of the people. Majer quotes from a remarkable 1827 play inspired by the giraffe, in which a lady’s maid abandons her domestic duties to see the giraffe, crying, “I am French! I have a right to see the Giraffe; she is national property” [40]. Although a gift to the king, this giraffe was clearly viewed as ultimately belonging to the people of France.

This process was augmented by the fact that, by the 1820s, the press --including the fashion press -- was flourishing. This was particularly conducive to the widespread dissemination of information and imagery of the giraffe. The newspapers treated her as a continuing major news story [37], and her representation appeared in thousands of lithographs, engravings and woodcuts. She also constantly appeared as a vehicle for satiric criticism of the king, particularly by those opposed to his censorship laws.

A third factor was the particular relationship that France had with Egypt. French interest in that country had been strong ever since Napoleon’s invasion in 1798, with the associated awakening of interest in Egyptian culture being spurred by the publication of the massive, magnificently illustrated ten-volume Description de l’Ėgypte [38]. Even further impetus was provided by Champollion’s decipherment of the Rosetta Stone in 1822. All this meant that by 1826 the French public was already well acquainted culturally and politically with giraffe’s country of origin [39].

Finally, the giraffe’s wide public visibility and accessibility over a prolonged period of time – from the walk across France itself, her daily walks, and from her public exhibition in the centrally located (and free) Jardin des Plantes. Far from being secreted away in the king’s private estate, she became a giraffe of the people. Majer quotes from a remarkable 1827 play inspired by the giraffe, in which a lady’s maid abandons her domestic duties to see the giraffe, crying, “I am French! I have a right to see the Giraffe; she is national property” [40]. Although a gift to the king, this giraffe was clearly viewed as ultimately belonging to the people of France.

Winners and losers

Although the giraffe was a popular sensation in France, she turned out to be a total failure in influencing public or official French opinion in favour of Ali, as Drovetti had hoped. Although Ali’s gift had become the most famous animal in France, none of her popularity rubbed off on him or on his Greek exploits. In fact, within a week of the giraffe’s arrival in Paris, the European powers, acting from a variety of political reasons, had signed a treaty against Ali and the Turks, and sent a fleet off to Greece. Despite Drovetti’s last-minute manoeuvring, the fleet reached Greece in October and, in the Battle of Navarino, lasting just a few hours, destroyed the Ottoman fleet [41]. It was a turning point in the revolution which would see Greece eventually get recognition as an independent state in 1832.

The giraffe also did little for the reputation of the French King. Instead of her gentility rubbing off on him, the opposite occurred -- those opposed to the King exploited the giraffe’s animal nature. So, for example, a medallion was struck with the notation that “nothing has changed in France; there is only one more beast” [42]. Another satirist caricatured the King as a giraffe, with the caption “the largest beast one has ever seen” [43]. In time, this royal connection would, in turn, contribute to the dimming of the giraffe’s own lustre.

However, some people profited. Certainly, girafamania merchandisers did well. The wily Drovetti, for his part, also managed to survive and even prosper from the affair, on the basis that he, not Ali, should be given the credit for securing the giraffe for France. He also inveigled himself into French royal favour by selling the King his second huge collection of Egyptian antiquities. He died a rich man in 1852.

Ali himself would go on to conquer Syria, but it was a victory he later had to relinquish after a subsequent attack on his Ottoman masters in Constantinople went seriously awry. Commonly regarded as the founder of modern Egypt because of his military, economic and cultural reforms, he died senile in 1849.

The giraffe also did little for the reputation of the French King. Instead of her gentility rubbing off on him, the opposite occurred -- those opposed to the King exploited the giraffe’s animal nature. So, for example, a medallion was struck with the notation that “nothing has changed in France; there is only one more beast” [42]. Another satirist caricatured the King as a giraffe, with the caption “the largest beast one has ever seen” [43]. In time, this royal connection would, in turn, contribute to the dimming of the giraffe’s own lustre.

However, some people profited. Certainly, girafamania merchandisers did well. The wily Drovetti, for his part, also managed to survive and even prosper from the affair, on the basis that he, not Ali, should be given the credit for securing the giraffe for France. He also inveigled himself into French royal favour by selling the King his second huge collection of Egyptian antiquities. He died a rich man in 1852.

Ali himself would go on to conquer Syria, but it was a victory he later had to relinquish after a subsequent attack on his Ottoman masters in Constantinople went seriously awry. Commonly regarded as the founder of modern Egypt because of his military, economic and cultural reforms, he died senile in 1849.

|

As for the giraffe, it continued to enjoy popular attention for a few years but, in the way of all crazes, its popularity faded in an era in which constant novelty was craved. Even more astounding marvels would soon emerge -- photography would be invented, trains would start running, communications would be revolutionised by the electric telegraph [44].

By 1830, the giraffe’s popularity had declined to the point where Balzac would caustically observe that she was visited only by “retarded provincials, bored nannies and simple and naïve fellows” [45]. |

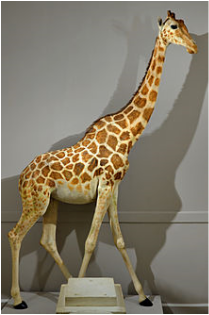

After the giraffe died in 1845, her body was stuffed, and stood for decades on display in the foyer of the museum at the Jardin des Plantes. The artist Eugène Delacroix commented that the giraffe had died “in obscurity as complete as his [sic] entry had been brilliant”, and “here he [sic] was, all stiff and clumsy as nature made him [sic]” [46].

In truth, however, the giraffe has turned out to be not as obscure as either Balzac or Delacroix might have thought. In fact, in more recent times her story has been re-discovered, and she has enjoyed somewhat of a revival blaze of publicity, becoming the subject of a number of books, starting with Gabriel Dardaud’s Une Girafe Pour Le Roi (1985), followed by Michael Allin’s Zarafa (1998) and Olivier Lebleu’s Les Avatars de Zarafa (2006]; a number of children’s books (for example, Judith St George, Zarafa, the giraffe who walked to the King); numerous scholarly articles; a major exhibition (La veritable histoire de Zarafa, the Musee du Jardin des Plantes, 2012), a full-length animated film (Zarafa, 2012); and even a puppet play (Tall Horse, 2004 [47].

You can still see the giraffe today at her final resting place in the Museum of Natural History at La Rochelle (Fig 11). Both Balzac and Delacroix would no doubt be surprised to hear that she has become the emblem of the museum, and to this day remains a star attraction.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2013

You can hear Philip speaking about this article on Derek Mooney’s documentary broadcast on 26/12/22 on Irish RTÉ Radio 1. It’s available at https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22190081/

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The art of giraffe diplomacy", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

For more Journal articles on Egypt, see:

· Egyptian Blue: the colour of technology

· The Life and Death of Mummy Brown

· Lost masterpieces of ancient Egyptian art from the Nebamun tomb-chapel

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

In truth, however, the giraffe has turned out to be not as obscure as either Balzac or Delacroix might have thought. In fact, in more recent times her story has been re-discovered, and she has enjoyed somewhat of a revival blaze of publicity, becoming the subject of a number of books, starting with Gabriel Dardaud’s Une Girafe Pour Le Roi (1985), followed by Michael Allin’s Zarafa (1998) and Olivier Lebleu’s Les Avatars de Zarafa (2006]; a number of children’s books (for example, Judith St George, Zarafa, the giraffe who walked to the King); numerous scholarly articles; a major exhibition (La veritable histoire de Zarafa, the Musee du Jardin des Plantes, 2012), a full-length animated film (Zarafa, 2012); and even a puppet play (Tall Horse, 2004 [47].

You can still see the giraffe today at her final resting place in the Museum of Natural History at La Rochelle (Fig 11). Both Balzac and Delacroix would no doubt be surprised to hear that she has become the emblem of the museum, and to this day remains a star attraction.

© Philip McCouat 2015, 2013

You can hear Philip speaking about this article on Derek Mooney’s documentary broadcast on 26/12/22 on Irish RTÉ Radio 1. It’s available at https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22190081/

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The art of giraffe diplomacy", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

For more Journal articles on Egypt, see:

· Egyptian Blue: the colour of technology

· The Life and Death of Mummy Brown

· Lost masterpieces of ancient Egyptian art from the Nebamun tomb-chapel

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

end notes

1. Molly Oldfield, “The First Giraffe in France”, in The Secret Museum, Collins, London, 2013 at 124ff.

2. See our article, Early Influences of Photography.

3. Now called Istanbul.

4. Brian M Fagan, The Rape of the Nile, McDonald and Jane’s, London 1977 at 82.

5. Fagan, op cit at 82.

6. Michael Allin, Zarafa, Headline, London, 1998 at 48.

7. Fagan, op cit at 85. See also our article, The Life and Death of Mummy Brown.

8. Allin, op cit at 67.

8a. On panda diplomacy, see Marina Belozerskaya, The Medici Giraffe, Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2006, at 376ff.

9. Edmund Blair Bolles, A Second Way of Knowing: the Riddle of Human Perception, cited in Belozerskaya, op cit, at 107-8.

10. Berthold Laufer, The Giraffe in History and Art, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, 1928 at 5, 21 [accessed at https://archive.org/details/giraffeinhistory27lauf]

11. Laufer, op cit at 26.

12. Gavin Menzies, 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, Bantam Press, London, 2002 at 32. Giraffes started being mentioned in Chinese literature from the 12th century.

13. Laufer, op cit at 50.

14. See generally “Caesar’s Giraffe”: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/giraffe.html

15. Laufer, op cit at 58.

16. See generally Belozerskaya, op cit at 107-131.

17. Laufer, op cit at 80.

18. Belozerskaya, op cit at 128. At the time she said this, she was sadly unaware that the giraffe was already dead.

19. Allin, op cit at 96.

19a. Actually two calves were captured but the second, intended to be used to curry favour with the British, was frailer. Partly crippled by her period of being bound, she was unable to support her own weight, did not thrive and died shortly after reaching England.

20. Allin, op cit at 70.

21. Allin, op cit at 6ff.

22. The size of giraffes varies dramatically according to their species. The smallest subspecies of giraffe is the Masai. Other subspecies include the mid-size Rothschild and the large Reticulated which grows up to 20 feet high and weighs 3,000 pounds, making it the tallest land animal: see Allin, op cit at 70.

22a. You can see a sitting Atir in Fig 1.

23. Giraffes are normally calm and gentle, though have a formidable kick when threatened. Their main enemies are lions and, at waterholes, crocodiles.

24. Allin, op cit at 116.

25. Allin, op cit at 136.

26. Allin, op cit at 8.

27. Heather J. Sharkey “La Belle Africaine: The Sudanese Giraffe Who Went to France" https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00083968.2015.1043712 Allin op cit at 5 stated, probably mistakenly, that zarafa also meant “charming” or “lovely one”: see Denys Johnson-Davies, “Journey of a Giraffe”, review of Allin.

28. Allin, op cit at 145.

29. Allin, op cit at 156.

30. Allin, op cit at 175.

31. Allin, op cit at 128.

32. Michele Majer, "La Mode à la girafe: Fashion, Culture, and Politics in Bourbon Restoration France", Studies in Decorative Arts 17:1 (Fall-Winter 2009-10): 123-161.

33. Allin, op cit at 9.

34. Majer, op cit at 175.

35. Majer, op cit at 125.

36. Majer, op cit: see also Erik Ringmar, “Audience for a Giraffe: European Expansionism and the Quest for the Exotic”, Journal of World History, Vol 17, No 4, p 375.

37. Majer, op cit at 131.

38. See our article, The Life and Death of Mummy Brown.

39. Majer, op cit.

40. Majer, op cit at 127.

41. Allin, op cit at 182.

42. Ringmar, op cit at 386.

43. Lynn Sherr, Tall Blondes: A Book about Giraffes, Andrews McMeel Pub, Kansas City, 1997, at 108.

44. See our article, Art in a Speeded-up World.

45. Ringmar, op cit at 385.

46. Cited in Sherr, op cit at 108. Delacroix mistakenly thought the giraffe was a male.

47. See http://www.les-amis-de-zarafa.com/2010/06/tall-horse/

© Philip McCouat 2015

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The art of giraffe diplomacy", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME

2. See our article, Early Influences of Photography.

3. Now called Istanbul.

4. Brian M Fagan, The Rape of the Nile, McDonald and Jane’s, London 1977 at 82.

5. Fagan, op cit at 82.

6. Michael Allin, Zarafa, Headline, London, 1998 at 48.

7. Fagan, op cit at 85. See also our article, The Life and Death of Mummy Brown.

8. Allin, op cit at 67.

8a. On panda diplomacy, see Marina Belozerskaya, The Medici Giraffe, Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2006, at 376ff.

9. Edmund Blair Bolles, A Second Way of Knowing: the Riddle of Human Perception, cited in Belozerskaya, op cit, at 107-8.

10. Berthold Laufer, The Giraffe in History and Art, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, 1928 at 5, 21 [accessed at https://archive.org/details/giraffeinhistory27lauf]

11. Laufer, op cit at 26.

12. Gavin Menzies, 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, Bantam Press, London, 2002 at 32. Giraffes started being mentioned in Chinese literature from the 12th century.

13. Laufer, op cit at 50.

14. See generally “Caesar’s Giraffe”: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/giraffe.html

15. Laufer, op cit at 58.

16. See generally Belozerskaya, op cit at 107-131.

17. Laufer, op cit at 80.

18. Belozerskaya, op cit at 128. At the time she said this, she was sadly unaware that the giraffe was already dead.

19. Allin, op cit at 96.

19a. Actually two calves were captured but the second, intended to be used to curry favour with the British, was frailer. Partly crippled by her period of being bound, she was unable to support her own weight, did not thrive and died shortly after reaching England.

20. Allin, op cit at 70.

21. Allin, op cit at 6ff.

22. The size of giraffes varies dramatically according to their species. The smallest subspecies of giraffe is the Masai. Other subspecies include the mid-size Rothschild and the large Reticulated which grows up to 20 feet high and weighs 3,000 pounds, making it the tallest land animal: see Allin, op cit at 70.

22a. You can see a sitting Atir in Fig 1.

23. Giraffes are normally calm and gentle, though have a formidable kick when threatened. Their main enemies are lions and, at waterholes, crocodiles.

24. Allin, op cit at 116.

25. Allin, op cit at 136.

26. Allin, op cit at 8.

27. Heather J. Sharkey “La Belle Africaine: The Sudanese Giraffe Who Went to France" https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00083968.2015.1043712 Allin op cit at 5 stated, probably mistakenly, that zarafa also meant “charming” or “lovely one”: see Denys Johnson-Davies, “Journey of a Giraffe”, review of Allin.

28. Allin, op cit at 145.

29. Allin, op cit at 156.

30. Allin, op cit at 175.

31. Allin, op cit at 128.

32. Michele Majer, "La Mode à la girafe: Fashion, Culture, and Politics in Bourbon Restoration France", Studies in Decorative Arts 17:1 (Fall-Winter 2009-10): 123-161.

33. Allin, op cit at 9.

34. Majer, op cit at 175.

35. Majer, op cit at 125.

36. Majer, op cit: see also Erik Ringmar, “Audience for a Giraffe: European Expansionism and the Quest for the Exotic”, Journal of World History, Vol 17, No 4, p 375.

37. Majer, op cit at 131.

38. See our article, The Life and Death of Mummy Brown.

39. Majer, op cit.

40. Majer, op cit at 127.

41. Allin, op cit at 182.

42. Ringmar, op cit at 386.

43. Lynn Sherr, Tall Blondes: A Book about Giraffes, Andrews McMeel Pub, Kansas City, 1997, at 108.

44. See our article, Art in a Speeded-up World.

45. Ringmar, op cit at 385.

46. Cited in Sherr, op cit at 108. Delacroix mistakenly thought the giraffe was a male.

47. See http://www.les-amis-de-zarafa.com/2010/06/tall-horse/

© Philip McCouat 2015

Mode of citation: Philip McCouat, "The art of giraffe diplomacy", Journal of Art in Society, www.artinsociety.com

We welcome your comments on this article

Back to HOME